Libera me

A man walks into his bar and finds...no one there.

A man walks into his bar and finds...no one there.

OK, so the "man" was me, and the "bar" was a Reddit-descended IRC channel devoted to tennis...but the shock of emptiness was the same. Because tennis is a global sport, this channel hosts people from Syracuse NY, Britain, Indonesia, the Netherlands. There is always someone commenting, checking the weather wherever tennis is playing, checking scores, or shooting (or befriending) the channel's frequent flying ducks.

Not now: blank, empty void, like John Oliver's background for the last, no-audience year. Those eight listed users are there in nickname only.

A year ago at this time, this channel's users were comparing pandemic restrictions. In our lockdowns, I liked knowing there was always someone in another time zone to type to in real time. So: slight panic. Where *are* they?

IRC dates to the old cooperative Internet. It's a protocol, not a service, so anyone can run an IRC server, and many people do, even though the mainstream, especially the younger mainstream, long since moved on through instant messaging and on to Twitter, WhatsApp groups, Telegram channels, Slack, and Discord. All of these undoubtedly look prettier and are easier to use, but the base functionality hasn't changed all that much.

IRC's enduring appeal is that it's all plain text and therefore bandwidth-light, it can host any size of conversation from a two-person secret channel to a public channel of thousands, multiple clients are available on every platform, and it's free. Genuinely free, not pay-with-data free - no ads! Accordingly, it's still widely used in the open source community. Individual channels largely set their own standards and community norms...and their own games. Circa 2003, I played silly trivia quizzes on a TV-related channel. On this one...ducks. A sample:

゜゜・。 。・゜゜\_o< FLAP FLAP!

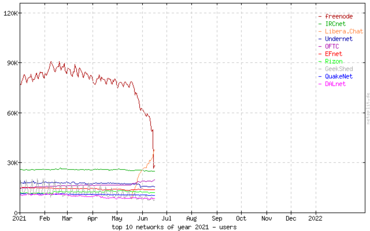

However, the fact that anyone *can* run their own server doesn't mean that everyone *does*, and like other Internet services (see also: open web, email), IRC gravitated towards larger networks that enable discovery. If you host your own server, strangers can only find it if you let them; on a large network users can search for channels, find topics they're interested in, and connect to the nearest server. While many IRC networks still survive, in recent years by far the biggest, according to Netsplit, is Freenode, largely because of its importance in providing connections and support for the open source community. Freenode is also where the missing tennis channel was hosted until about Tuesday, three days before I noticed it was silent. As you'll see in the Netsplit image above, that was when Freenode traffic plummeted, countered by a near-vertical rise in traffic on Libera Chat. That is where my channel turned out to be restored to its usual bustling self.

What happened is both complicated and pretty simple: ownership changed hands without anyone's quite realizing what it was going to mean. To say that IRC is free to use does not mean there are no costs: besides computers and bandwidth, the owners of IRC servers must defend their networks against attacks. Freenode, Wikipedia explains, began as a Linux support channel on another network run by four people, who went on to set up their own network, which eventually became the largest support network for the open source community. A series of ownership changes led from a California charity through a couple of steps to today's owner, the UK-based private company Freenode Ltd, which is owned by Andrew Lee, a technology entrepreneur and founder of the Private Internet Access VPN. No one appears to have thought much about this until last month, when 20 to 30 of the volunteers who run Freenode ("staff") resigned accusing Lee of executing a hostile takeover. Some of them promptly set up Libera as an alternative.

What makes this story about a somewhat arcane piece of the old Internet interesting - aside from the book that demands to be written about IRC's rich history, culture, and significance - is that this is the second time in the last 18 months that a significant piece of the non-profit infrastructure has been targeted for private ownership. The other was the .org top-level domain. These underpinnings need better protection.

On the day traffic plummeted, Lee made deciding to move really easy: as part of changing the network's underlying software, he decided to remove the entire database of registered names and channels - committing suicide, some called it. Because, really: if you're going to have to reregister and reconstruct everything anyway, the barrier to moving to that identical new network over there with all the familiar staff and none of the new owner mishegoss is gone. Hence the mass exodus.

This is why IRC never spawned a technology giant: no lock-in. Normally when you move a conversation it dies. In this case, the entire channel, with its scripts and games and familiar interface, could be recreated at speed and resume as if nothing had happened. All they had to do was tell people. Five minutes after I posted a plaintive query on Reddit, someone came to retrieve me.

So, now: a woman logs into an IRC channel and finds all the old regulars. A duck flaps past. I have forgotten the ".bang" command. I type ".bef" instead. The duck is saved.

Illustrations: Netsplit's graph of IRC network traffic from June 2021.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.