Ghosted

Three months after the arrival into force of Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, Nieman Lab finds that more than 1,000 US newspapers are still blocking EU visitors.

Three months after the arrival into force of Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, Nieman Lab finds that more than 1,000 US newspapers are still blocking EU visitors.

"We are engaged on the issue", says the placard that blocks access to even the front pages of the New York Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, both owned by Tronc, as well as the Los Angeles Times, which was owned by Tronc until very recently. Ironically, Wikipedia tells us that the silly-sounding name "Tronc" was derived from "Tribune Online Content"; you'd think a company whoe name includes "online" would grasp the illogic of blocking 500 million literate readers. Nieman Lab also notes that Tronc is for sale, so I guess the company has more urgent problems.

Also apparently unable to cope with remediating its systems, despite years of notice, is Lee Enterprises, which owns numerous newspapers including the Carlisle, PA Sentinel and the Arizona Daily Star; these return "Error 451: Unavailable due to legal reasons", and blame GDPR as the reason "access cannot be granted at this time". Even the giant retail chain Williams-Sonoma has decided GDPR is just too hard, redirecting would-be shoppers to a UK partner site that is almost, but not quite, entirely unlike Williams-Sonoma - and useless if you want to ship a gift to someone in the US.

If you're reading this in the US, and you want to see what we see, try any of those URLs in a free proxy such as Hide Me, setting set your location to Amsterdam. Fun!

Less humorously, shortly after GDPR came into force a major publisher issued new freelance contracts that shift the liability for violations onto freelances. That is, if I do something that gets the company sued for GDPR violations, in their world I indemnify them.

And then there are the absurd and continuing shenanigans of ICANN, which is supposed to be a global multi-stakeholder modeling a new type of international governance, but seems so unable to shake its American origins that it can't conceive of laws it can't bend to its will.

Years ago, I recall that the New York Times, which now embraces being global, paywalled non-US readers because we were of no interest to their advertisers. For that reason, it seems likely that Tronc and the others see little profit in a European audience. They're struggling already; it may be hard to justify the expenditure on changing their systems for a group of foreign deadbeats. At the same time, though, their subscribers are annoyed that they can't access their home paper while traveling.

On the good news side, the 144 local daily newspapers and hundreds of other publications belonging to GateHouse Media seem to function perfectly well. The most fun was NPR, which briefly offered two alternatives: accept cookies or view in plain text. As someone commented on Twitter, it was like time-traveling back to 1996.

The intended consequence has been to change a lot of data practices. The Reuters Institute finds that the use of third-party cookies is down 22% on European news sites in the three months GDPR has been in force - and 45% on UK news sites. A couple of days after GDPR came into force, web developer Marcel Freinbichler did a US-vs-EU comparison on USA Today: load time dropped from 45 seconds to three, from 124 JavaScript files to zero, and a more than 500 requests to 34.

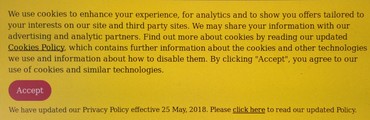

But many (and not just US sites) are still not getting the message, or are mangling it. For example, numerous sites now display boxes displaying the many types of cookies they use and offering chances to opt in or out. A very few of these are actually well-designed, so you can quickly opt out of whole classes of cookies (advertising, tracking...) and get on with reading whatever you came to the site for. Others are clearly designed to make it as difficult as possible to opt out; these sites want you to visit a half-dozen other sites to set controls. Still others say that if you click the button or continue using the site your consent will be presumed. Another group say here's the policy ("we collect your data"), click to continue, and offer no alternative other than to go away. Not a lawyer - but sites are supposed to obtain explicit consent for collecting data on an opt-in basis, not assume consent on an an opt-out basis while making it onerous to object.

But many (and not just US sites) are still not getting the message, or are mangling it. For example, numerous sites now display boxes displaying the many types of cookies they use and offering chances to opt in or out. A very few of these are actually well-designed, so you can quickly opt out of whole classes of cookies (advertising, tracking...) and get on with reading whatever you came to the site for. Others are clearly designed to make it as difficult as possible to opt out; these sites want you to visit a half-dozen other sites to set controls. Still others say that if you click the button or continue using the site your consent will be presumed. Another group say here's the policy ("we collect your data"), click to continue, and offer no alternative other than to go away. Not a lawyer - but sites are supposed to obtain explicit consent for collecting data on an opt-in basis, not assume consent on an an opt-out basis while making it onerous to object.

The reality is that it is far, far easier to install ad blockers - such as EFF's Privacy Badger - than to navigate these terrible user interfaces. In six months, I expect to see surveys coming from American site owners saying that most people agree to accept advertising tracking, and what they will mean is that people clicked OK, trusting their ad blockers would protect them.

None of this is what GDPR was meant to do. The intended consequence is to protect citizens and redress the balance of power; exposing exploitative advertising practices and companies' dependence on "surveillance capitalism" is a good thing. Unfortunately, many Americans seem to be taking the view that if they just refuse service the law will go away. That approach hasn't worked since Usenet.

Illustrations: Personally collected screenshots.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.