Parting gifts

All national constitutions are written to a threat model that is clearly visible if you compare what they say to how they are put into practice. Ireland, for example, has the same right to freedom of religion embedded in its constitution as the US bill of rights does. Both were reactions to English abuse, yet they chose different remedies. The nascent US's threat model was a power-abusing king, and that focus coupled freedom of religion with a bar on the establishment of a state religion. Although the Founding Fathers were themselves Protestants and likely imagined a US filled with people in their likeness, their threat model was not other beliefs or non-belief but the creation of a supreme superpower derived from merging state and church. In Ireland, for decades, "freedom of religion" meant "freedom to be Catholic". Campaigners for the separation of church and state in 1980s Ireland, when I lived there, advocated fortifying the constitutional guarantee with laws that would make it true in practice for everyone from atheists to evangelical Christians.

All national constitutions are written to a threat model that is clearly visible if you compare what they say to how they are put into practice. Ireland, for example, has the same right to freedom of religion embedded in its constitution as the US bill of rights does. Both were reactions to English abuse, yet they chose different remedies. The nascent US's threat model was a power-abusing king, and that focus coupled freedom of religion with a bar on the establishment of a state religion. Although the Founding Fathers were themselves Protestants and likely imagined a US filled with people in their likeness, their threat model was not other beliefs or non-belief but the creation of a supreme superpower derived from merging state and church. In Ireland, for decades, "freedom of religion" meant "freedom to be Catholic". Campaigners for the separation of church and state in 1980s Ireland, when I lived there, advocated fortifying the constitutional guarantee with laws that would make it true in practice for everyone from atheists to evangelical Christians.

England, famously, has no written constitution to scrutinize for such basic principles. Instead, its present Parliamentary system has survived for centuries under a "gentlemen's agreement" - a term of trust that in our modern era transliterates to "the good chaps rule of government". Many feel Boris Johnson has exposed the limitations of this approach. Yet it's not clear that a written constitution would have prevented this: a significant lesson of Donald Trump's US presidency is how many of the systems protecting American democracy rely on "unwritten norms" - the "gentlemen's agreement" under yet another name.

It turns out that tinkering with even an unwritten constitution is tricky. One such attempt took place in 2011, with the passage of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act. Without the act, a general election must be held at least once every five years, but may be called earlier if the prime minister advises the monarch to do so; they may also be called at any time following a vote of no confidence in the government. Because past prime ministers were felt to have abused their prerogative by timing elections for their political benefit, the act removed it in favor of a set five-year interval unless a no-confidence vote found a two-thirds super-majority. There were general elections in 2010 and 2015 (the first under the act). The next should have been in 2020. Instead...

No one counted on the 2016 vote to leave the EU or David Cameron's next-day resignation. In 2017, Theresa May, trying to negotiate a deal with an increasingly divided Parliament and thinking an election would win her a more workable majority and a mandate, got the necessary super-majority to call a snap election. Her reward was a hung Parliament; she spent the rest of her time in office hamstrung by having to depend on the good will of Northern Ireland's Democratic Unionist Party to get anything done. Under the act, the next election should have been 2022. Instead...

In 2019, a Conservative party leadership contest replaced May with Boris Johnson, who, after several failed attempts blocked by opposition MPs determined to stop the most reckless Brexit possibilities, won the necessary two-thirds majority and called a snap election, winning a majority of 80 seats. The next election should be in 2024. Instead...

They repealed the act in March 2022. As we were. Now, Johnson is going, leaving both party and country in disarray. An election in 2023 would be no surprise.

Watching the FTPA in action led me to this conclusion: British democracy is like a live frog. When you pin down one bit of it, as the FTPA did, it throws the rest into distortion and dysfunction. The obvious corollary is that American democracy is a *dead* frog that is being constantly dissected to understand how it works. The disadvantage to a written constitution is that some parts will always age badly. The advantage is clarity of expectations. Yet both systems have enabled someone who does not care about norms to leave behind a generation's worth of continuing damage.

All this is a long preamble to saying that last year's concerns about the direction of the UK's computers-freedom-privacy travel have not abated. In this last week before Parliament rose for the summer, while the contest and the heat saturated the news, Johnson's government introduced the Data Protection and Digital Information bill, which will undermine the rights granted by 25 years of data protection law. The widely disliked Online Safety bill was postponed until September. The final two leadership candidates are, to varying degrees, determined to expunge EU law, revamp the Human Rights act, and withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights. In addition, lawyer Gina Miller warns, the Northern Ireland Protocol bill expands executive power by giving ministers the Henry VIII power to make changes without Parliamentary consent: "This government of Brexiteers are eroding our sovereignty, our constitution, and our ability to hold the government to account."

The British convention is that "government" is collective: the government *are*. Trump wanted to be a king; Johnson wishes to be a president. The coming months will require us to ensure that his replacement knows their place.

Illustrations: Final leadership candidates Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss in debate on ITV.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

An unexpected bonus of the gradual-then-sudden disappearance of Boris Johnson's government, followed by

An unexpected bonus of the gradual-then-sudden disappearance of Boris Johnson's government, followed by

_nave_left_-_Monument_to_Doge_Giovanni_Pesaro_-_Statue_of_the_Doge-thumb-370x294-1111.jpg)

"If voting changed anything, they'd abolish it, the maverick British left-wing politician

"If voting changed anything, they'd abolish it, the maverick British left-wing politician

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...

"Regulatory oversight is going to be inevitable,"

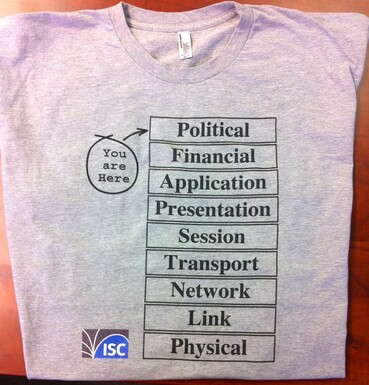

"Regulatory oversight is going to be inevitable,"  The financial revolution due to hit Britain in mid-January has had surprisingly little publicity and has little to do with the money-related things making news headlines over the last few years. In other words, it's not a new technology, not even a cryptocurrency. Instead, this revolution is regulatory: banks will be required to open up access to their accounts to third parties.

The financial revolution due to hit Britain in mid-January has had surprisingly little publicity and has little to do with the money-related things making news headlines over the last few years. In other words, it's not a new technology, not even a cryptocurrency. Instead, this revolution is regulatory: banks will be required to open up access to their accounts to third parties. As anyone attending the annual

As anyone attending the annual