Trading digital rights

Until this week I hadn't fully appreciated the number of ways Brexiting UK is trapped between the conflicting demands of major international powers of the size it imagines itself still to be. On the question of whether to allow Huawei to participate in building the UK's 5G network, the UK is caught between the US and China. On conditions of digital trade - especially data protection - the UK is trapped between the US and the EU with Northern Ireland most likely to feel the effects. This was spelled out on Tuesday in a panel on digital trade and trade agreements convened by the Open Rights Group.

Until this week I hadn't fully appreciated the number of ways Brexiting UK is trapped between the conflicting demands of major international powers of the size it imagines itself still to be. On the question of whether to allow Huawei to participate in building the UK's 5G network, the UK is caught between the US and China. On conditions of digital trade - especially data protection - the UK is trapped between the US and the EU with Northern Ireland most likely to feel the effects. This was spelled out on Tuesday in a panel on digital trade and trade agreements convened by the Open Rights Group.

ORG has been tracking the US-UK trade negotiations and their effect on the UK's continued data protection adequacy under the General Data Protection Regulation. As discussed here before, the basic problem with respect to privacy is that outside the state of California, the US has only sector-specific (mainly health, credit scoring, and video rentals) privacy laws, while the EU regards privacy as a fundamental human right, and for 25 years data protection has been an essential part of implementing that right.

In 2018 when the General Data Protection Regulation came into force, it automatically became part of British law. On exiting the EU at the end of January, the UK replaced it with equivalent national legislation. Four months ago, Boris Johnson said the UK intends to develop its own policies. This is risky; according to Oliver Patel and Nathan Lea at UCL, 75% of the UK's data flows are with the EU (PDF). Deviation from GDPR will mean the UK will need the EU to issue an adequacy ruling that the UK's data protection framework is compatible. The UK's data retention and surveillance policies may make obtaining that adequacy decision difficult; as Anna Fielder pointed out in Tuesday's discussion, this didn't arise before because national security measures are the prerogative of EU member states. The alternatives - standard contractual clauses and binding corporate rules - are more expensive to operate, are limited to the organization that uses them, and are being challenged in the European Court of Justice.

So the UK faces a quandary: does it remain compatible with the EU, or choose the dangerous path of deviation in order to please its new best friend, the US? The US, says Public Citizen's Burcu Kilic, wants unimpeded data flows and prohibitions on requirements for data localization and disclosure of source code and algorithms (as proposals for regulating AI might mandate).

It is easy to see these issues purely in terms of national alliances. The bigger issue for Kilic - and for others such as Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue - is the inclusion of these issues in trade agreements at all, a problem we've seen before with intellectual property provisions. Even when the negotiations aren't secret, which they generally are, international agreements are relatively inflexible instruments, changeable only via the kinds of international processes that created them. The result is to severely curtail the ability of national governments and legislatures to make changes - and the ability of civil society to participate. In the past, most notably with respect to intellectual property rights, corporate interests' habit of shopping their desired policies around from country to country until one bit and then using that leverage to push the others to "harmonize" has been called "policy laundering". This is a new and updated version, in which you bypass all that pesky, time-consuming democracy nonsense. Getting your desired policies into a trade agreement gets you two - or more - countries for the price of one.

In the discussion, Javier Ruiz called it "forum shifting" and noted that the latest example is intermediary liability, which is included in the US-Mexico-Canada agreement that replaced NAFTA. This is happening just as countries - including the US - are responding to longstanding problems of abuse on online platforms by considering how to regulate the big online platforms - in the US, the debate is whether and how to amend S230 of the Communications Decency Act, which offers a shield against intermediary liability, in the UK it's the online harms bill and the age-appropriate design code.

Every country matters in this game. Kilic noted that the US is also in the process of negotiating a trade deal with Kenya that will also include digital trade and intellectual property - small in and of itself, but potentially the model for other African deals - and for whatever deal Kenya eventually makes with the UK.

Kilic traces the current plans to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which included the US during the Obama administration and which attracted public anger over provisions for investor-state dispute settlement. On assuming the presidency, Trump withdrew, leaving the other countries to recreate it as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was formally signed in March 2018. There has been some discussion of the idea that a newly independent Britain could join it, but it's complicated. What the US wanted in TPP, Kilic said, offers a clear guide to what it wants in trade agreements with the UK and everywhere else - and the more countries enter into these agreements, the harder it becomes to protect digital rights. "In trade world, trade always comes first."

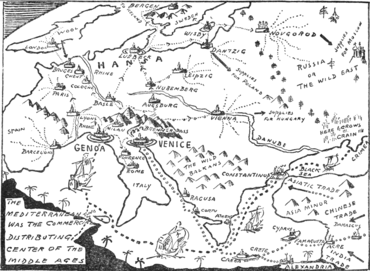

Illustrations: Medieval trade routes (from The Story of Mankind, 1921).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.