Hate week

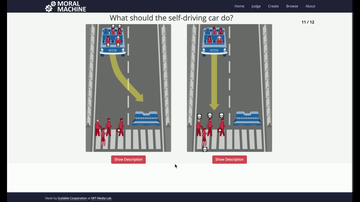

When, say ten years from now, someone leaks the set of rules by which self-driving cars make decisions about how to behave in physical-world human encounters of the third kind, I suspect they're going to look like a mess of contradictions and bizarre value judgements. I doubt they'll look anything like MIT's Moral Machine experiment, which aims to study the ethical principles we might like such cars to follow. Instead, they will be absurd-seeming patches of responses to mistakes and resemble much more closely Richard Stallman's contract rider. They will be the self-driving car equivalent of "Please don't buy me a parrot" or "Please just leave me alone when I cross streets", and, if exposed in leaked documents for public study without explanation of the difficulties that generated them, people will marvel, "How messed-up is that?"

When, say ten years from now, someone leaks the set of rules by which self-driving cars make decisions about how to behave in physical-world human encounters of the third kind, I suspect they're going to look like a mess of contradictions and bizarre value judgements. I doubt they'll look anything like MIT's Moral Machine experiment, which aims to study the ethical principles we might like such cars to follow. Instead, they will be absurd-seeming patches of responses to mistakes and resemble much more closely Richard Stallman's contract rider. They will be the self-driving car equivalent of "Please don't buy me a parrot" or "Please just leave me alone when I cross streets", and, if exposed in leaked documents for public study without explanation of the difficulties that generated them, people will marvel, "How messed-up is that?"

The tangle of leaked guides and training manuals for Facebook moderators that the Guardian has been studying this week is a case in point. How can it be otherwise for a site with 1.94 billion users in 150? countries, each with its own norms and legal standards, all of which depend on context and must filter through Facebook's own internal motivators. Images of child abuse are illegal almost everywhere, but Napalm Girl, the 1972 nude photo of nine-year-old Kim Phuc, is a news photograph whose deletion sparks international outrage and therefore restoration. Holocaust denial is illegal in 14 countries; according to Facebook's presentation, it geoblocks such content in just the four countries that pursue legal action: Germany, France, Israel, and Austria. In the US, of course, it's legal, and "Congress may make no law...".

Automation will require deriving general principles from this piece-by-piece process - a grammar of acceptable human behavior - so that it can be applied across an infinite number of unforeseeable contexts. Like the Google raters Annalee Newitz profiled for Ars Technica a few weeks ago, most of Facebook's content moderators are subcontracted. As the Guardian reports, they have nothing like the training or support that the Internet Watch Foundation provides to its staff. Plus, their job is much more complicated: the IWF's remit is specifically limited to child abuse images and focuses on whether or not the material that's been reported to it is illegal. That is a much narrower question than whether something is "extremist", yet the work sounds just as traumatic. "Every day, every minute, that's what you see. Heads being cut off," one moderator tells the Guardian.

Automation will require deriving general principles from this piece-by-piece process - a grammar of acceptable human behavior - so that it can be applied across an infinite number of unforeseeable contexts. Like the Google raters Annalee Newitz profiled for Ars Technica a few weeks ago, most of Facebook's content moderators are subcontracted. As the Guardian reports, they have nothing like the training or support that the Internet Watch Foundation provides to its staff. Plus, their job is much more complicated: the IWF's remit is specifically limited to child abuse images and focuses on whether or not the material that's been reported to it is illegal. That is a much narrower question than whether something is "extremist", yet the work sounds just as traumatic. "Every day, every minute, that's what you see. Heads being cut off," one moderator tells the Guardian.

Wired has found The Moderators, a short documentary by Adrian Chen and Ciaran Cassidy that shows how the world's estimated 150,000 social media content moderators are trained. The filmed group are young, Indian, mostly male, and in their first jobs. The video warns that the images we see them consider are disturbing; but isn't it also disturbing that lower-paid laborers in the Global South are being tasked with removing images considered too upsetting for Westerners?

A couple of weeks ago, in a report on online hate crime, the Home Affairs Select Committee lambasted social media companies for "not doing more". Among its complaints was the recommendation that social media companies should publish regular reports detailing the number of staff, the number of complaints, and how these were resolved. As Alec Muffett responded, how many humans is a 4,000-node computer cluster? In a separate posting, Muffett, a former Facebook engineer, tried to explain the sheer mathematical scale of the problem. It's yuge. Bigly.

A related question is whether Facebook - or any commercial company - on its own should be the one to solve it and what kind of collateral damage "solving it" might inflict. The HASC report argued that if social media companies don't proactively remove hateful content then they should be forced to pay for police to do it for them. Let's say that in newspapers: "If newspapers don't do more to curb hateful speech they will have to pay police to do it for them." Viewed that way, it's a lot easier to parse this into: If you do not censor yourselves the government will do it for you. This is a threat very like the one leveled at Internet Service Providers in the UK in 1996, when the big threat in town was thought to be Usenet. The result was the creation of the IWF, which occupies a grey area between government and private company. IWF is not particularly transparent or accountable, but it does have a check on its work in the form of the police, who are the arbiters of whether a piece of content is illegal - and, eventually, the courts, if somene is brought to trial. Most of Facebook's decisions about its daily billions of pieces of content have no such check: most of what's at issue here falls in the grey areas child protection experts insist should not exist.

I am no fan of Facebook, and assume that its values as a company are designed to serve primarily the interests of its shareholders and advertisers, but I can find some sympathy for it in facing these conundrums. When Monika Bickert, head of global policy management, writes about the difficulty of balancing safety and freedom, she sounds reasonable, as Joe Fingas writes at Engadget. This is a genuinely hard problem: they are trying to parse human nature.

Illustrations: MIT's Moral Machine; Mark Zuckerberg

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

_(cropped)-thumb-200x240-519.jpg)