The Algernon problem

Last week we noted that it may be a sign of a maturing robotics industry that it's possible to have companies specializing in something as small as fingertips for a robot hand. This week, the workshop day kicking off this year's We Robot conference provides a different reason to think the same thing: more and more disciplines are finding their way to this cross-the-streams event. This year, joining engineers, computer scientists, lawyers, and the odd philosopher are sociologists, economists, and activists.

Last week we noted that it may be a sign of a maturing robotics industry that it's possible to have companies specializing in something as small as fingertips for a robot hand. This week, the workshop day kicking off this year's We Robot conference provides a different reason to think the same thing: more and more disciplines are finding their way to this cross-the-streams event. This year, joining engineers, computer scientists, lawyers, and the odd philosopher are sociologists, economists, and activists.

The result is oddly like a meeting of the Research Institute for the Science of Cyber Security, where a large part of the point from the beginning has been that human factors and economics are as important to good security as technical knowledge. This was particularly true in the face-off between the economist Rob Seamans and the sociologist Beth Bechky, which pitted quantitative "things we can count" against qualitative "study the social structures" thinking. The range of disciplines needed to think about what used to be "computer" security keeps growing as the ways we use computers become more complex; robots are computer systems whose mechanical manifestations interact with humans. This move has to happen.

One sign is a change in language. Madeline Elish, currently in the news for her newly published 2016 We Robot paper, Moral Crumple Zones, said she's trying to replace the term "deploying" with "integrating" for arriving technologies. "They are integrated into systems," she explained, "and when you say "integrate" it implies into what, with whom, and where." By conrast, "deployment" is military-speak, devoid of context. I like this idea, since by 2015, it was clear from a machine learning conference at the Royal Society that many had begun seeing robots as partners rather than replacements.

Later, three Japanese academics - the independent researcher Hideyuki Matsumi, Takayuki Kato, and Pumio Shimpo - tried to explain why Japanese people like robots so much - more, it seems, than "we" do (whoever "we" are). They suggested three theories: the influence of TV and manga; the influence of the mainstream Shinto religion, which sees a spirit in everything; and the Japanese government strategy to make the country a robotics powerhouse. The latter has produced a 356-page guideline for research development.

"Japanese people don't like to draw distinctions and place clear lines," Shinto said. "We think of AI as a friend, not an enemy, and we want to blur the lines." Shimpo had just said that even though he has two actual dogs he wants an Aibo. Kato dissented: "I personally don't like robots."

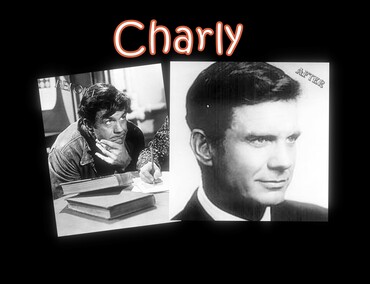

The MIT researcher Kate Darling, who studies human responses to robots, found positive reinforcement in studies that have found that autistic kids respond well to robots. "One theory is that they're social, but not too social." An experiment that placed these robots in homes for 30 days last summer had "stellar results". But: when the robots were removed at the end of the experiment, follow-up studies found that the kids were losing the skills the robots had brought them. The story evokes the 1958 Daniel Keyes story Flowers for Algernon, but then you have to ask: what were the skills? Did they matter to the children or just to the researchers and how is "success" defined?

The opportunities anthropomorphization opens for manipulation are an issue everywhere. Woody Hartzog called the tendency to believe what the machine says "automation bias", but that understates the range of motivations: you may believe the machine because you like it, because it's manipulated you, or because you're working in a government benefits agency where you can't be sure you won't get fired if you defy the machine's decision. Would that everyone could see Bill Smart and Cindy Grimm follow up their presentation from last year to show: AI is just software; it doesn't "know" things; and it's the complexity that gets you. Smart hates the term "autnomous" for robots "because in robots it means deterministic software running on a computer. It's teleoperation via computer code."

This is the "fancy hammer" school of thinking about robots, and it can be quite valuable. Kevin Bankston soon demonstrated this: "Science fiction has trained us to worry about Skynet instead of housing discrimination, and expect individual saviors rather than communities working together to deal with community problems." AI is not taking our jobs; capitalists are using AI to take our jobs - a very different problem. As long as we see robots and AI as autonomous, we miss that instead they ares agents carrying out others' plans. This is a larger example of a pervasive problem with smartphones, social media sites, and platforms generally: they are designed to push us to forget the data-collecting, self-interested, manipulative behemoth behind them.

Returning to Elish's comment, we are one of the things robots integrate with. At the moment, this is taking the form of making random people research subjects: the pedestrian killed in Arizona by a supposedly self-driving car, the hapless prisoners whose parole is decided by it's-just-software, the people caught by the Metropolitan Police's staggeringly flawed facial recognition, the homeless people who feel threatened by security robots, the Caltrain passengers sharing a platform with an officious delivery robot. Did any of us ask to be experimented on?

Illustrations: Cliff Robertson in Charly, the movie version of "Flowers for Algernon".

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.