Lost for words

Privacy advocacy has the effect of making you hyper-conscious of the exponentially increasing supply of data. All sorts of activities that used to leave little or no trace behind now create a giant stream of data exhaust, from interactions with friends (now captured by social media companies), to TV viewing (now captured by streaming services and cable companies), where and when we travel (now captured by credit card companies, municipal smart card systems, and facial recognition-equipped cameras), and everything we buy (unless you use cash). And then there are the vast amounts of new forms of data being gathered by the sensors attached to Internet of Things devices and, increasingly, more intimate devices, such as medical implants.

Privacy advocacy has the effect of making you hyper-conscious of the exponentially increasing supply of data. All sorts of activities that used to leave little or no trace behind now create a giant stream of data exhaust, from interactions with friends (now captured by social media companies), to TV viewing (now captured by streaming services and cable companies), where and when we travel (now captured by credit card companies, municipal smart card systems, and facial recognition-equipped cameras), and everything we buy (unless you use cash). And then there are the vast amounts of new forms of data being gathered by the sensors attached to Internet of Things devices and, increasingly, more intimate devices, such as medical implants.

And yet. In a recent paper (PDF) that Tammy Xu summarizes at MIT Technology Review, the EPOCH AI research and forecasting unit argues that we are at risk of running out of a particular kind of data: the stuff we use to train large language models. More precisely, the stock of data deemed suitable for use in language training datasets is growing more slowly than the size of the datasets these increasingly large and powerful models require for training. The explosion of privacy-invasive, mechanically captured data mentioned above doesn't help with this problem; it can't help train what today passes for "artificial intelligence to improve its ability to generate content that reads like it could have been written by a sentient human.

So in this one sense the much-debunked saw that "data is the new oil" is truer than its proponents thought. Like drawing water from aquifers or depleting oil reserves, data miners have been relying on capital resources that have taken eras to build up and that can only be replenished over similar time scales. We professional writers produce new "high-quality" texts too slowly.

As Xu explains, "high-quality" in this context generally means things like books, news articles, scientific papers, and Wikipedia pages - that is, the kind of prose researchers want their models to copy. Wikipedia's English language section makes up only 0.6% of GPT-3 training data. "Low-quality" is all the other stuff we all churn out: social media postings, blog postings, web board comments, and so on. There is of course vastly more of this (and some of it is, we hope, high-quality)..

The paper's authors estimate that the high-quality text modelers prefer could be exhausted by 2026. Images, which are produced at higher rates, will take longer to exhaust - lasting to perhaps between 2030 and 2040. The paper considers three options for slowing exhaustion: broaden the standard for acceptable quality; find new sources; and develop more data-efficient solutions for training algorithms. Pursuing the fossil fuel analogy, I guess the equivalents might be: turning to techniques such as fracking to extract usable but less accessible fossil fuels, developing alternative sources such as renewables, and increasing energy efficiency. As in the energy sector, we may need to do all three.

I suppose paying the world's laid-off and struggling professional writers to produce text to feed the training models can't form part of the plan?

The first approach might have some good effects by increasing the diversity of training data. The same is true of the second, although using AI-generated text (synthetic data to train the model seems as recursive as using an algorithm to highlight trends to tempt users. Is there anything real in there?

Regarding the third... It's worth remembering the 2020 paper On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? (the paper over which Google apparently fired AI ethics team leader Timnit Gebru). In this paper (and a FaCCT talk), Gebru, Emily M. Bender, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell outlined the escalating environmental and social costs of increasingly large language models and argued that datasets needed to be carefully curated and documented, and tailored to the circumstances and context in which the model was eventually going to be used.

As Bender writes at Medium, there's a significant danger that humans reading the language generated by systems like GPT-3 may *believe* it's the product of a sentient mind. At IAI News, she and Chirag Shah call text generators like GPT-3 dangerous because they have no understanding of meaning even as they spit out coherent answers to user questions in natural language. That is, these models can spew out plausible-sounding nonsense at scale; in 2020, Renée DiResta predicted at The Atlantic that generative text will provide an infinite supply of disinformation and propaganda.

This is humans finding patterns even where they don't exist: all the language model does is make a probabilistic guess about the next word based on statistics derived from the data it's been trained on. It has no understanding of its own results. As Ben Dickson puts it at TechTalks as part of an analysis of the workings of the language model BERT, "Coherence is in the eye of the beholder." On Twitter, Bender quipped that a good new name would be PSEUDOSCI (for Pattern-matching by Syndicate Entities of Uncurated Data Objects, through Superfluous (energy) Consumption and Incentives).

If running out of training data means a halt on improving the human-like quality of language generators' empty phrases, that may not be such a bad thing.

Illustrations: Drunk parrot (taken by Simon Bisson).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Why is robotics hard?

Why is robotics hard? Years ago, an alarmist book about cybersecurity threats concluded with the suggestion that attackers' expertise at planting backdoors could result in a "zero day" when, at an attacker-specified time, all the world's computers could be shut down simultaneously.

Years ago, an alarmist book about cybersecurity threats concluded with the suggestion that attackers' expertise at planting backdoors could result in a "zero day" when, at an attacker-specified time, all the world's computers could be shut down simultaneously. This week: short cuts.

This week: short cuts. What if,

What if,

It's only an accident of covid that this year's

It's only an accident of covid that this year's

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...

_in_Luxembourg_with_flags-thumb-370x277-576.jpg) We rarely talk about it this way, but sometimes what makes a computer secure is a matter of perspective. Two weeks ago, at the

We rarely talk about it this way, but sometimes what makes a computer secure is a matter of perspective. Two weeks ago, at the

At the Guardian,

At the Guardian,

"My iPhone won't stab me in my bed,"

"My iPhone won't stab me in my bed,"

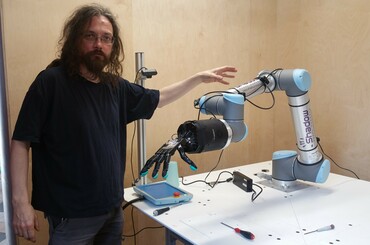

Getting to Shadow Robot's present state involved narrowing down the dream founder

Getting to Shadow Robot's present state involved narrowing down the dream founder -thumb-370x288-822.jpg)

In movies and TV shows, robot assistants are humanoids, but that future is too far away to help the onrushing 4.8 million. Today's care-oriented robots have biological, but not human, inspirations: the

In movies and TV shows, robot assistants are humanoids, but that future is too far away to help the onrushing 4.8 million. Today's care-oriented robots have biological, but not human, inspirations: the

-thumb-270x360-798.jpg)

In the memorable panel "We Know Where You Will Live" at the 1996

In the memorable panel "We Know Where You Will Live" at the 1996

My favourite new term from this year's

My favourite new term from this year's

"All sensors are terrible,"

"All sensors are terrible,"

A couple of weeks ago, I was asked to talk to a

A couple of weeks ago, I was asked to talk to a  "We were kids working on the new stuff," said Kevin Werbach. "Now it's 20 years later and it still feels like that."

"We were kids working on the new stuff," said Kevin Werbach. "Now it's 20 years later and it still feels like that." Both

Both  The financial revolution due to hit Britain in mid-January has had surprisingly little publicity and has little to do with the money-related things making news headlines over the last few years. In other words, it's not a new technology, not even a cryptocurrency. Instead, this revolution is regulatory: banks will be required to open up access to their accounts to third parties.

The financial revolution due to hit Britain in mid-January has had surprisingly little publicity and has little to do with the money-related things making news headlines over the last few years. In other words, it's not a new technology, not even a cryptocurrency. Instead, this revolution is regulatory: banks will be required to open up access to their accounts to third parties. As anyone attending the annual

As anyone attending the annual  Would you rather be killed by a human or a machine?

Would you rather be killed by a human or a machine?

-thumb-220x247-646.jpg)