Lost in transition

"Why do I have to scan my boarding card?" I demanded loudly of the machine that was making this demand. "I'm buying a thing of milk!"

"Why do I have to scan my boarding card?" I demanded loudly of the machine that was making this demand. "I'm buying a thing of milk!"

The location was Heathrow Terminal 5. The "thing of milk" was a pint of milk being purchased with a view to a late arrival in a continental European city where tea is frequently offered with "Kafeesahne", a thick, off-white substance that belongs with tea about as much as library paste does.

A human materialized out of nowhere, and typed in some codes. The transaction went through. I did not know you could do that.

The incident sounds minor - yes, I thanked her - but has a real point. For years, UK airport retailers secured discounts for themselves by demanding to scan boarding cards at the point of purchase while claiming the reason was to exempt the customers from VAT when they are taking purchases out of the country. Just a couple of years ago the news came out: the companies were failing to pass the resulting discounts on to customers and simply pocketing the VAT. Legally, you are not required to comply with the request.

They still ask, of course.

If you're dealing with a human retail clerk, refusing is easy: you say "No" and they move on to completing the transaction. The automated checkout (which I normally avoid), however is not familiar with No. It is not designed for No. No is not part of its vocabulary unless a human comes along with an override code.

My legal right not to scan my boarding card therefore relies on the presence of an expert human. Take the human out of that loop - or overwhelm them with too many stations to monitor - and the right disappears, engineered out by automation and enforced by the time pressure of having to catch a flight and/or the limited resource of your patience.

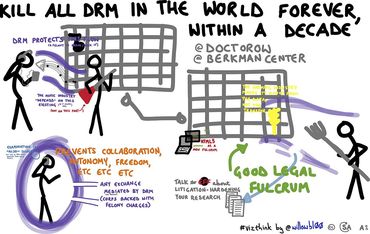

This is the same issue that has long been machinified by DRM - digital rights management - and the locks it applies to commercially distributed content. The text of Alice in Wonderland is in the public domain, but wrap it in DRM and your legal rights to copy, lend, redistribute, and modify all vanish, automated out with no human to summon and negotiate with.

Another example: the discount railcard I pay for once a year is renewable online. But if you go that route, you are required to upload your passport, photo driver's license, or national ID card. None of these should really be necessary. If you renew at a railway station, you pay your money and get your card, no identification requested. In this example the automation requires you to submit more data and take greater risk than the offline equivalent. And, of course, when you use a website there's no human to waive the requirement and restore the status quo.

Each of these services is designed individually. There is no collusion, and yet the direction is uniform.

Most of the discussion around this kind of thing - rightly - focuses on clearly unjust systems with major impact on people's lives. The COMPAS recidivism algorithm, for example, is used to risk-assess the likelihood that a criminal defendant will reoffend. A ProPublica study found that the algorithm tended to produced biased results of two kinds: first, black defendants were more likely than white defendants to be incorrectly rated as high risk; second, white reoffenders were incorrectly classified as low-risk more often than black ones. Other such systems show similar biases, all for the same basic reason: decades of prejudice are baked into the training data these systems are fed. Virginia Eubanks, for example, has found similar issues in systems such as those that attempt to identify children at risk and that appear to see poverty itself as a risk factor.

By contrast, the instances I'm pointing out seem smaller, maybe even insignificant. But the potential is that over time wide swathes of choices and rights will disappear, essentially automated out of our landscape. Any process can be gamed this way.

At a Royal Society meeting last year, law professor Mireille Hildebrandt outlined the risks of allowing the atrophy of governance through the text-driven law that today is negotiated in the courts. The danger, she warned, is that through machine deployment and "judgemental atrophy" it will be replaced with administration, overseen by inflexible machines that enforce rules with no room for contestability, which Hildebrandt called "the heart of the rule of law".

What's happening here is, as she said, administration - but it's administration in which our legitimate rights dissipate in a wave of "because we can" automated demands. There are many ways we willingly give up these rights already - plenty of people are prepared to give up anonymity in financial transactions by using all manner of non-cash payment systems, for example. But at least those are conscious choices from which we derive a known benefit. It's hard to see any benefit accruing from the loss of the right to object to unreasonable bureaucracy imposed upon us by machines designed to serve only their owners' interests.

Illustrations: "Kill all the DRM in the world within a decade" (via Wikimedia.).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.