The laws they left behind

In the spring of 2020, as country after country instituted lockdowns, mandated contact tracing, and banned foreign travelers, many, including Britain, hastily passed laws enabling the state to take such actions. Even in the strange airlessness of the time, it was obvious that someday there would have to be a reckoning and a reevaluation of all that new legislation. Emergency powers should not be allowed to outlive the emergency. I spent many of those months helping Privacy International track those new laws across the world.

In the spring of 2020, as country after country instituted lockdowns, mandated contact tracing, and banned foreign travelers, many, including Britain, hastily passed laws enabling the state to take such actions. Even in the strange airlessness of the time, it was obvious that someday there would have to be a reckoning and a reevaluation of all that new legislation. Emergency powers should not be allowed to outlive the emergency. I spent many of those months helping Privacy International track those new laws across the world.

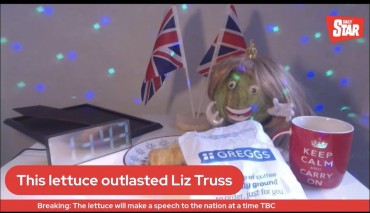

Here in 2022, although Western countries believe the acute emergency phase of the pandemic is past, the reality is that covid is still killing thousands of people a week across the world, and there is no guarantee we're safe from new variants with vaccine escape. Nonetheless, the UK and US at least appear to accept this situation as if it were the same old "normal". Except: there's a European war, inflation, strikes, a cost of living crisis, energy shortages, and a load of workplace monitoring and other privacy invasions that would have been heavily resisted in previous times. (And, in the UK, a government that has lost its collective mind; as I type no one dares move the news cameras away from the doors of Number 10 Downing Street in case the lettuce wins.)

Laws last longer than pandemics, as the human rights lawyer Adam Wagner writes in his new book, Emergency State: How We Lost Our Freedoms in the Pandemic and Why It Matters. For the last couple of years, Wagner has been a constant presence in my Twitter feed, alongside numerous scientists and health experts posting and examining the latest new research. Wagner studies a different pathology: the gaps between what the laws actually said and what was merely guidance. and between overactive police enforcement and people's reasonable beliefs of what the laws should be.

In Emergency State, Wagner begins by outlining six characteristics of the power of emergency-empowered state: mighty, concentrated, ignorant, corrupt, self-reinforcing, and, crucially, we want it to happen. As a comparison, Wagner notes the surveillance laws and technologies rapidly adopted after 9/11. Much of the rest of the book investigates a seventh characteristic: these emergency-expanded states are hard to reverse. In an example that's frequently come up here, see Britain's World War II ID card, which took until 1952 to remove, and even then it took Harry Wilcock to win in court after refusing to show his papers on demand.

Most of us remember the shock and sudden silence of the first lockdown. Wagner remembers something most of us either didn't know or forgot: when Boris Johnson announced the lockdown and listed the few exceptional circumstances under which we were allowed to leave home, there was as yet no law in place on which law enforcement could rely. That only came days later. The emergency to justify this was genuine: dying people were filling NHS hospital beds. And yet: the government response overturned the basis of Britain's laws, which traditionally presume that everything is permitted unless it's specifically forbidden. Suddenly, the opposite - everything is forbidden unless explicitly permitted - was the foundation of daily life. And it happened with no debate.

Wagner then works methodically through Britain's Emergency State, beginning by noting that the ethos of Boris Johnson's government, continuing the conservatives' direction of travel, coincidentally was already disdainful of Parliamentary scrutiny (see also: prorogation of Parliament) and ready to weaken both the human rights act and the judiciary. As the pandemic wore on, Parliamentary attention to successive waves of incoming laws did not improve; sometimes, the laws had already changed by the time they reached the chamber. In two years, Parliament failed to amend any of them. Meanwhile, Wagner notes, behind closed doors government members ignored the laws they made.

The press dubbed March 18, 2022 Freedom Day, to signify the withdrawal of all restrictions. And yet: if scientists' worst fears come true, we may need them again. Many covid interventions - masks, ventilation, social distancing, contact tracing - are centuries old, because they work. The novelty here was the comprehensive lockdowns and widespread business closures, which Wagner suggests may have come about because the first country to suffer and therefore to react was China, where this approach was more acceptable to its authoritarian government. Would things have gone differently had the virus surfaced in a democratic country? We will never know. Either way, the effects of the cruelest restrictions - the separation among families and friends, the isolation imposed on the elderly and dying - cannot be undone.

In Britain's case, Wagner points to flaws in the Public Health Act (1984) that made it too easy for a months-old prime minister with a distaste for formalities to bypass democratic scrutiny. He suggests four remedies: urgently amend the act to include safeguards; review all prosecutions and fines under the various covid laws; codify stronger human rights, either in a written constitution or a bill of rights; and place human rights at the heart of emergency decision making. I'd add: elect leaders who will transparently explain which scientific advice they have and haven't followed and why, and who will plan ahead. The Emergency State may be in abeyance, but current UK legislation in progress seeks to undermine our rights regardless.

Illustrations: The Daily Star's QE2 lettuce declaring victory as 44-day prime minister Liz Truss resigns.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Bad ideas never die.

Bad ideas never die. All national constitutions are written to a threat model that is clearly visible if you compare what they say to how they are put into practice. Ireland, for example, has the same right to freedom of religion embedded in its constitution as the US bill of rights does. Both were reactions to English abuse, yet they chose different remedies. The nascent US's threat model was a power-abusing king, and that focus coupled freedom of religion with a bar on the establishment of a state religion. Although the Founding Fathers were themselves Protestants and likely imagined a US filled with people in their likeness, their threat model was not other beliefs or non-belief but the creation of a supreme superpower derived from merging state and church. In Ireland, for decades, "freedom of religion" meant "freedom to be Catholic". Campaigners for the separation of church and state in 1980s Ireland, when I lived there, advocated fortifying the constitutional guarantee with laws that would make it true in practice for everyone from atheists to evangelical Christians.

All national constitutions are written to a threat model that is clearly visible if you compare what they say to how they are put into practice. Ireland, for example, has the same right to freedom of religion embedded in its constitution as the US bill of rights does. Both were reactions to English abuse, yet they chose different remedies. The nascent US's threat model was a power-abusing king, and that focus coupled freedom of religion with a bar on the establishment of a state religion. Although the Founding Fathers were themselves Protestants and likely imagined a US filled with people in their likeness, their threat model was not other beliefs or non-belief but the creation of a supreme superpower derived from merging state and church. In Ireland, for decades, "freedom of religion" meant "freedom to be Catholic". Campaigners for the separation of church and state in 1980s Ireland, when I lived there, advocated fortifying the constitutional guarantee with laws that would make it true in practice for everyone from atheists to evangelical Christians. An unexpected bonus of the gradual-then-sudden disappearance of Boris Johnson's government, followed by

An unexpected bonus of the gradual-then-sudden disappearance of Boris Johnson's government, followed by -thumb-370x246-1150.jpg)

On February 28, at the same time as he

On February 28, at the same time as he

-thumb-370x277-1083.jpg)

The clowder of legislation to restrict voting access that's popping up across the US is casting the last 20 years of debate over online voting in a new light.

The clowder of legislation to restrict voting access that's popping up across the US is casting the last 20 years of debate over online voting in a new light.

-thumb-200x300-915.jpg) As the year gets going, two conflicts look like setting precedents for Internet regulation: Australia's push to require platforms to pay license fees for linking to their articles; and Facebook's pending decision whether to make former president Donald Trump's ban permanent, as Twitter already has.

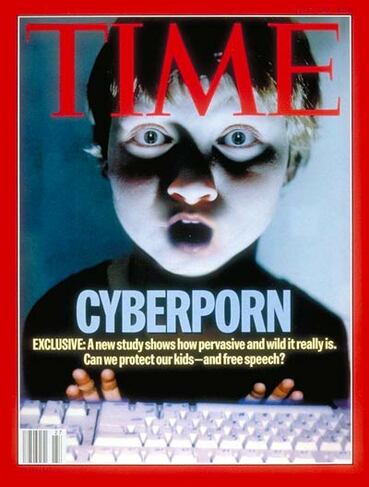

As the year gets going, two conflicts look like setting precedents for Internet regulation: Australia's push to require platforms to pay license fees for linking to their articles; and Facebook's pending decision whether to make former president Donald Trump's ban permanent, as Twitter already has. In many ways, this 1,000th net.wars column is much like the first (the count is somewhat artificial, since net.wars began as a 1998

In many ways, this 1,000th net.wars column is much like the first (the count is somewhat artificial, since net.wars began as a 1998

-thumb-370x369-968.jpg)

"Can you keep a record of every key someone enters?"

"Can you keep a record of every key someone enters?"

To these known evils, the German Pirate Party MEP

To these known evils, the German Pirate Party MEP

"Regulatory oversight is going to be inevitable,"

"Regulatory oversight is going to be inevitable,"  A couple of weeks ago, I was asked to talk to a

A couple of weeks ago, I was asked to talk to a  There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones,

There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones,  The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article

The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article

It was Farrell's comment, though, that sparked the realization that fake news cannot be solved by thinking of it as a problem in only one of the fields of journalism, international relations, economic inequality, market forces, or technology. It is all those things and more, and we will not make any progress until we take an approach that combines all those disciplines.

It was Farrell's comment, though, that sparked the realization that fake news cannot be solved by thinking of it as a problem in only one of the fields of journalism, international relations, economic inequality, market forces, or technology. It is all those things and more, and we will not make any progress until we take an approach that combines all those disciplines.