The Internet as we know it

It's another of those moments when people to whom the Internet is still a distinctive and beloved medium fret that it's about to be violently changed into all everything they were glad it wasn't when it began. That this group is a minority is in itself a sign. Circa 1994, almost every Internet user was its defender. Today, for most people, the Internet just *is* and ever has been - until someone comes along and wants to delete their favorite service.

It's another of those moments when people to whom the Internet is still a distinctive and beloved medium fret that it's about to be violently changed into all everything they were glad it wasn't when it began. That this group is a minority is in itself a sign. Circa 1994, almost every Internet user was its defender. Today, for most people, the Internet just *is* and ever has been - until someone comes along and wants to delete their favorite service.

Fears of splintering the Internet are as old as the network itself. Different people have focused on different mechanisms: TV and radio-style corporate takeover (see for example Robert McChesney's work); incompatible censorship and data protection regimes, technical incompatibilities born of corporate overreach, and so on. In 2013, four seemed significant: copyright, localizing data storage (data protection), censorship; losing network neutrality, and splitting the addressing system.

Then, the biggest threats appeared to be structural censorship and losing network neutrality. Both are still growing. In 2019, Access Now says, 213 Internet shutdowns in 33 countries collectively disrupted 1,706 days of Internet access. No one imagined this in the 1990s, when all countries vied to reap the benefits of getting their citizens online. More conceivable were government regulation, shifting technological standards, corporate ownership, copyright laws, and unequal access...but we never expected the impact of the eventual convergence with the mobile world, a clash of cultures that got serious after 2010, when social media and smartphones began mutually supercharging.

A couple of weeks ago, James Ball introduced a new threat, writing disapprovingly about US president Donald Trump's executive order declaring the video-sharing app TikTok a national emergency. Ball rightly calls this ban "generational vandalism, but then he writes that banning an app solely because of the nationality of its owner, he writes, "could be an existential threat to the Internet as we know it".

If that's true, then the Internet is already not "the Internet as we know it". So much depends on when your ideas of "the Internet" were formed and where you live. As Ball himself acknowledges in his new book, The System: Who Owns the Internet and How It Owns Us, in some countries Facebook is synonymous with the Internet because of the zero-rating deals the company has struck with mobile phone operators. In China, "the Internet", contrary to what most people believed was possible in the 1990s, is a giant, firewalled nationally controlled space. TikTok, as primarily a mobile phone app lives in a highly curated "the Internet" of app stores. Finally, even though "the Internet" in the 1990s sense is still with us in that people can still build their new ideas, most people's "the Internet" is now confined to the same few sites that exercise extraordinary control over what is read, seen, and heard.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission's new draft News Media Bargaining Code provides an example. It requires Google and Facebook (and, eventually, others) to negotiate in good faith to pay news media companies for use of their content when users share links and snippets. Unlike Spain's previous similar attempt, Google can't escape by shutting down its news service because it also serves up news through its search engine and YouTube. Facebook has said it will block Australian users from sharing local or international news on Facebook and Instagram if the code becomes mandatory. But, as Alex Hern writes, the problem is that "One of the big ways that Facebook and Google have been bad for the news industry has been by becoming indispensable to the news industry". Australia can push this code into force, but when it does Google won't pay publishers *and* publishers will lose most of their traffic, exactly as happened in Spain and Germany. But misinformation will flourish.

This is still an upper network layer problem, albeit simplified by corporate monopoly. On the 1995-2010 web, there would be too many site owners to contend with, just as banning apps (see also India) is vastly simplified by needing to negotiate with just two app store owners. Censoring the open Internet required China to build a national firewall and hire maintainers while millions of new sites and services arrived every day. When they started, no one believed it could even be done.

The mobile world is not and never has been "the Internet as we know it", built to facilitate openness for scientists. Telephone companies have always been happiest with controlled systems and walled gardens, and before 2006, manufacturers like Nokia, Motorola, and Psion had to tailor their offerings to telco specifications. The iPhone didn't just change the design and capabilities of the slab in your hand; it also changed the makeup and power structures of the industry as profoundly as the PC had changed computing before it.

But these are still upper layers. Far more alarming, as Milton Mueller writes at the Internet Governance Project, is Trump's policy of excluding Chinese businesses from Internet infrastructure - and China's ideas for "new IP". This is a crucialthreat to the interoperable bedrock of "the network of all networks". As the Internet Society explains, it is that cooperative architecture "with no central authority" that made the Internet so successful. This is the first principle that built the Internet as we know it.

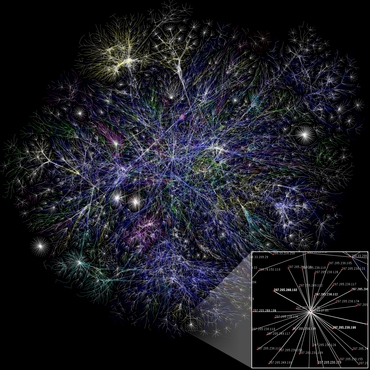

Illustrations: Map of the Internet circa 2005 (via The Opte Project at Wikimedia Commons.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.