New music

The news this week that "AI" "wrote" a song "in the style of" Nick Cave (who was scathing about the results) seemed to me about on a par with the news in the 1970s that the self-proclaimed medium Rosemary Brown was able to take dictation of "new works" by long-dead famous composers. In that: neither approach seems likely to break new artistic ground.

The news this week that "AI" "wrote" a song "in the style of" Nick Cave (who was scathing about the results) seemed to me about on a par with the news in the 1970s that the self-proclaimed medium Rosemary Brown was able to take dictation of "new works" by long-dead famous composers. In that: neither approach seems likely to break new artistic ground.

In Brown's case, musicologists, psychologists, and skeptics generally converged on the belief that she was channeling only her own subconscious. AI doesn't *have* a subconscious...but it does have historical inputs, just as Brown did. You can say "AI" wrote a set of "song lyrics" if you want, but that "AI" is humans all the way down: people devised the algorithms and wrote the computer code, created the historical archive of songs on which the "AI" was trained, and crafted the prompt that guided the "AI"'s text generation. But "the machine did it by itself" is a better headline.

Meanwhile...

Forty-two years after the first one, I have been recording a new CD (more details later). In the traditional folk world, which is all I know, getting good recordings is typically more about being practiced enough to play accurately while getting the emotional performance you want. It's also generally about very small budgets. And therefore, not coincidentally, a whole lot less about sound effects and multiple overdubs.

These particular 42 years are a long time in recording technology. In 1980, if you wanted to fix a mistake in the best performance you had by editing it in from a different take where the error didn't appear, you had to do it with actual reels of tape, an edit block, a razor blade, splicing tape...and it was generally quicker to rerecord unless the musician had died in the interim. Here in digital 2023, the studio engineer notes the time codes, slices off a bit of sound file, and drops it in. Result! Also: even for traditional folk music, post-production editing has a much bigger role.

Autotune, which has turned many a wavering tone into perfect pitch, was invented in 1997. The first time I heard about it - it alters the pitch of a note without altering the playback speed! - it sounded indistinguishable from magic. How was this possible? It sounded like artificial intelligence - but wasn't.

The big, new thing now, however, *is* "AI" (or what currently passes for it), and it's got nothing to do with outputting phrases. Instead, it's stem splitting - that is, the ability to take a music file that includes multiple instruments and/or voices, and separate out each one so each can be edited separately.

Traditionally, the way you do this sort of thing is you record each instrument and vocal separately, either laying them down one at a time or enclosing each musician/singer into their own soundproof booth, from where they can play together by listening to each other over headphones. For musicians who are used to singing and playing at the same time in live performance, it can be difficult to record separate tracks. But in recording them together, vocal and instrumental tracks tend to bleed into each other - especially when the instrument is something like an autoharp, where the instrument's soundboard is very close to the singer's mouth. Bleed means you can't fix a small vocal or instrumental error without messing up the other track.

With stem splitting, now you can. You run your music file through one of the many services that have sprung up, and suddenly you have two separated tracks to work with. It's being described to me as a "game changer" for recording. Again: sounds indistinguishable from magic.

This explanation makes it sound less glamorous. Vocals and instruments whose frequencies don't overlap can be split out using masking techniques. Where there is overlap, splitting relies on a model that has been trained on human-split tracks and that improves with further training. Still a black box, but now one that sounds like so many other applications of machine learning. Nonetheless, heard in action it's startling: I tried LALAL_AI on a couple of tracks, and the separation seemed perfect.

There are some obvious early applications of this. As the explanation linked above notes, stem splitting enables much finer sampling and remixing. A singer whose voice is failing - or who is unavailable - could nonetheless issue new recordings by laying their old vocal over a new instrumental track. And vice-versa: when, in 2002, Paul Justman wanted to recreate the Funk Brothers' hit-making session work for Standing in the Shadows of Motown, he had to rerecord from scratch to add new singers. Doing that had the benefit of highlighting those musicians' ability and getting them royalties - but it also meant finding replacements for the ones who had died in the intervening decades.

I'm far more impressed by the potential of this AI development than of any chatbot that can put words in a row so they look like lyrics. This is a real thing with real results that will open up a world of new musical possibilities. By contrast, "AI"-written song lyrics rely on humans' ability to conceive meaning where none exists. It's humans all the way up.

Illustrations: Nick Cave in 2013 (by Amanda Troubridge, via Wikimedia).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

This week provided two examples of the dangers of believing too much hype about modern-day automated systems and therefore overestimating what they can do.

This week provided two examples of the dangers of believing too much hype about modern-day automated systems and therefore overestimating what they can do.

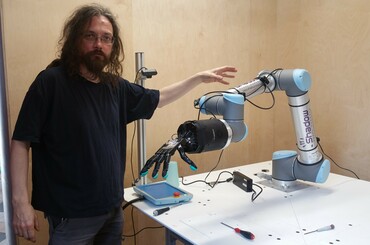

Getting to Shadow Robot's present state involved narrowing down the dream founder

Getting to Shadow Robot's present state involved narrowing down the dream founder