Becoming a science writer

As an Association of British Science Writers board member, I occasionally speak to science PhD students and postdocs about science writing. Since the most recent of these excursions was just this week, I thought I'd summarize some of what I've said.

To trained scientists aiming to make the switch: you are starting from a more knowledgeable place than the arts graduates who mostly populate this field. You already know how to investigate and add to a complex field of study, have a body of knowledge from which to reliably evaluate new claims, and know the significant contributors to your field and adjacent ones. What you need to learn are basic journalism skills such as interviewing, identifying stories, pitching them to venues where they might fit, remaining on the right side of libel law, and journalistic ethics and culture. Your new deadlines will seem really short!

Figuring out what kind of help you need is where an organization like the ABSW (and its counterparts in other countries) can help, first by offering opportunities for networking with other science writers, and second by providing training and resources. ABSW maintains, for example, a page that includes some basics and links.

Besides that, if you put "So You Want to Be a Science Writer" into your favorite search engine, you will find many guides from reputable sources such as other science writers' associations and university programs. I particularly like Ivan Oransky's talk for the National Association of Science Writers, because he begins with "my first failures".

Every career path is idiosyncratic enough that no one can copy its specifics. I began my writing career by founding The Skeptic magazine in 1987. Through the skeptics, I met all sorts of people, including one who got me my first writing-related job as a temporary subeditor on a computer magazine. Within weeks, I knew the editors of all the other magazines on its floor, and began writing features for them. In 1991, when I got online and sent my first email, I decided to specialize on the Internet because it was obviously the future of communication. A friend advises that if you find a fast-moving field, there will always be people willing to pay you to explain it to them.

So: I self-published, networked early and often - I joined the ABSW as soon as I was qualified - and luckily landed on a green field at the beginning of a complex and far-reaching social, cultural, political, and technological revolution. Today's early-career science writers will have to work harder to build their own networks than in the early 1990s, when we all met regularly at press conferences and shows - but they have vastly further reach than we had.

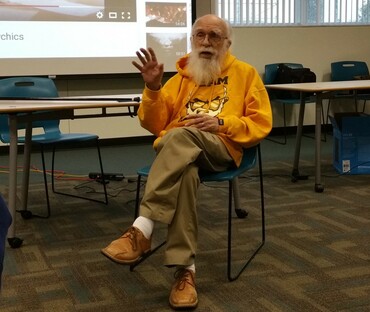

I have never had a job, so I can't tell people how to get one. I can, however, observe that if you focus solely on traditional media you will be aiming at a shrinking number of slots. Think more broadly about what science communication is, who does it, and in what context. The kind of journalism that used to be the sole province of newspapers and news magazines now has a home in NGOs, who also hire people who can do solid research, crunch data, and think creatively about new areas for investigation. You should also broaden your idea of "media" and "science communication". Few can be Robin Ince or Richard Wiseman, who combine comedy, magic, and science into sell-out shows, but everyone can work in non-traditional contexts in which to communicate science.

At the moment, commercial money is going into podcasts; people are building big followings for niche interests on YouTube and through self-publishing ebooks; and constant tweeters are important communicators, as botanist James Wong proves every day. Edward Hasbrouck, at the National Writers Union, has published solid advice on writing for digital formats: look to build revenue streams. The Internet offers many opportunities, but, as Hasbrouck writes, many are invisible to traditional publishing; as he also writes, traditional employment is just one of writers' many business models.

The big difficulty for trained academics is rethinking how you approach telling a story. Forget the academic structure of: 1) here is what I am going to say; 2) this is what I'm saying; 3) this is my summary of what I just said. Instead, when writing for the general public, put your most important findings first and tell your specific audience why it matters to *them*. Then show why they can have confidence in your claim by explaining your methods and how your findings fit into the rest of the relevant body of scientific knowledge. (Do not use net.wars as your model!)

Over time, you will probably want to branch out into other fields. Do not fear this; you know how to learn a complex field, and if you can learn one you can learn another.

It's inevitable that you will make some mistakes. When it happens, do your best to correct them, learn from how you made them, and avoid making the same one again.

Finally just a couple of other resources. My favorite book on writing is William Goldman's Adventures in the Screen Trade. He has solid advice for story structure no matter what you're writing. A handout I wrote for a blogging workshop for scientists (PDF) has some (I hope, useful) writing tips. Good luck!

Illustrations: Magician James Randi communicates science, Florida 2016.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.