Matrices of numbers

The older man standing next to me was puzzled. "Can you drive it?"

The older man standing next to me was puzzled. "Can you drive it?"

He gestured at the VW Beetle-style car-like creation in front of us. Its exterior, except for the wheels and chassis, was stained glass. This car was conceived by the artist Desmond Wilcox, who surmised that by 2059 autonomous cars will be so safe that they will no longer need safety features such as bumpers and can be made of fragile materials. The sole interior furnishing, a bed, lets you sleep while in transit. In person, the car is lovely to look at. Utterly impractical today in 2019, and it always will be. The other cars may be safe, but come on: falling tree, extreme cold, hailstorm...kid with a baseball?

On being told no, it's an autonomous car that drives itself, my fellow visitor to the Science Museum's new exhibition, Driverless, looked dissatisfied. He appeared to prefer driving himself.

"It would look good with a light bulb inside it hanging at the back of the garden," he offered. It would. Bit big, though last week in San Francisco I saw a bigger superbloom.

"Driverless" is a modest exhibition by Science Museum standards, and unlike previous robot exhibitions, hardly any of these vehicles are ready for real-world use. Many are graded according to their project status: first version, early tests, real-world tests, in use. Only a couple were as far along as real-world tests.

Probably a third are underwater explorers. Among the exhibits: the (yellow submarine!) long-range Boaty McBoatface Autosub, which is meant to travel up to 2,000 km over several months, surfacing periodically to send information back to scientists. Both this and the underwater robot swarms are intended for previously unexplored hostile environments, such as underneath the Antarctic ice sheet.

Alongside these and Wilcox's Stained Glass Driverless Car of the Future was the Capri Mobility pod, the result of a project to develop on-demand vans that can shuttle up to four people along a defined route either through a pedestrian area or on public roads. Small Robot sent its Tom farm monitoring robot. And from Amsterdam came Roboat, a five-year research project to develop the first fleet of autonomous floating boats for deployment in Amsterdam's canals. These are the first autonomous vehicles I've seen that really show useful everyday potential for rethinking traditional shapes, forms, and functionality: their flat surfaces and side connectors allow them to be linked into temporary bridges a human can walk across.

There's also an app-controlled food delivery drone; the idea is you trigger it to drop your delivery from 20 meters up when you're ready to receive it. What could possibly go wrong?

On the fun side is Duckietown (again, sadly present only as an image), a project to teach robotics via a system of small, mobile robots that motor around a Lego-like "town" carrying small rubber ducks. It's compelling like model trains, and is seeking Kickstarter funding to make the hardware for wider distribution. This should have been the hands-on bit.

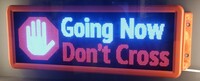

Previous robotics-related Science Museum exhibitions have asked as many questions as they answered. At that, this one is less successful.  Drive.ai's car-mounted warning signs, for example, are meant to tell surrounding pedestrians what its cars are doing. But are we really going to allow cars onto public roads (or even worse, pedestrian areas, like the Capri pods) to mow people down who don't see, don't understand, can't read, or willfully ignore the "GOING NOW; DON'T CROSS" sign? So we'll have to add sound: but do we want cars barking orders at us? Today, navigating the roads is a constant negotiation between human drivers, human pedestrians, and humans on other modes of transport (motorcycles, bicycles, escooters, skateboards...). Do we want a tomorrow where the cars have all the power?

Drive.ai's car-mounted warning signs, for example, are meant to tell surrounding pedestrians what its cars are doing. But are we really going to allow cars onto public roads (or even worse, pedestrian areas, like the Capri pods) to mow people down who don't see, don't understand, can't read, or willfully ignore the "GOING NOW; DON'T CROSS" sign? So we'll have to add sound: but do we want cars barking orders at us? Today, navigating the roads is a constant negotiation between human drivers, human pedestrians, and humans on other modes of transport (motorcycles, bicycles, escooters, skateboards...). Do we want a tomorrow where the cars have all the power?

In video clips researchers and commentators like Noel Sharkey, Kathy Nothstine, and Natasha Merat discuss some of these difficulties. Merat has an answer for the warning sign: humans and self-driving cars will have to learn each other's capabilities in order to peacefully coexist. This is work we don't really see happening today, and that lack is part of why I tend to think Christian Wolmar is right in predicting that these cars are not going to be filling our streets any time soon.

The placard for the Starship Bot (present only as a picture) advises that it cannot see above knee height, to protect privacy, but doesn't discuss the issues raised when Edward Hasbrouck encountered one in action. I was personally disappointed, after the recent We Robot discussion of the "monstrous" Moral Machine and its generalized sibling the trolley problem, to see it included here with less documentation than on the web. This matters, because the most significant questions about autonomous vehicles are going to be things like: what data do they collect about the people and things around them? To whom are they sending it? How long will it be retained? Who has the right to see it? Who has the right to command where these cars go?

More important, Sharkey says in a video clip, we must disentangle autonomous and remote-controlled vehicles, which present very different problems. Remote-controlled vehicles have a human in charge that we can directly challenge. By contrast, he said, we don't know why autonomous vehicles make the decisions they do: "They're just matrices of numbers."

Illustrations: Wilcox's stained glass car.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.