Septet

This week catches up on some things we've overlooked. Among them, in response to a Twitter comment: two weeks ago, on November 2, net.wars started its 18th unbroken year of Fridays.

This week catches up on some things we've overlooked. Among them, in response to a Twitter comment: two weeks ago, on November 2, net.wars started its 18th unbroken year of Fridays.

Last year, the writer and documentary filmaker Astra Taylor coined the term "fauxtomation" to describe things that are hyped as AI but that actually rely on the low-paid labor of numerous humans. In The Automation Charade she examines the consequences: undervaluing human labor and making it both invisible and insecure. Along these lines, it was fascinating to read that in Kenya, workers drawn from one of the poorest places in the world are paid to draw outlines around every object in an image in order to help train AI systems for self-driving cars. How many of us look at a self-driving car see someone tracing every pixel?

***

Last Friday, Index on Censorship launched Demonising the media: Threats to journalists in Europe, which documents journalists' diminishing safety in western democracies. Italy takes the EU prize, with 83 verified physical assaults, followed by Spain with 38 and France with 36. Overall, the report found 437 verified incidents of arrest or detention and 697 verified incidents of intimidation. It's tempting - as in the White House dispute with CNN's Jim Acosta - to hope for solidarity in response, but it's equally likely that years of politicization have left whole sectors of the press as divided as any bullying politician could wish.

***

We utterly missed the UK Supreme Court's June decision in the dispute pitting ISPs against "luxury" brands including Cartier, Mont Blanc, and International Watch Company. The goods manufacturers wanted to force BT, EE, and the three other original defendants, which jointly provide 90% of Britain's consumer Internet access, to block more than 46,000 websites that were marketing and selling counterfeits. In 2014, the High Court ordered the blocks. In 2016, the Court of Appeal upheld that on the basis that without ISPs no one could access those websites. The final appeal was solely about who pays for these blocks. The Court of Appeal had said: ISPs. The Supreme Court decided instead that under English law innocent bystanders shouldn't pay for solving other people's problems, especially when solving them benefits only those others. This seems a good deal for the rest of us, too: being required to pay may constrain blocking demands to reasonable levels. It's particularly welcome after years of expanded blocking for everything from copyright, hate speech, and libel to data retention and interception that neither we nor ISPs much want in the first place.

***

For the first time the Information Commissioner's Office has used the Computer Misuse Act rather than data protection law in a prosecution. Mustafa Kasim, who worked for Nationwide Accident Repair Services, will serve six months in prison for using former colleagues' logins to access thousands of customer records and spam the owners with nuisance calls. While the case reminds us that the CMA still catches only the small fry, we see the ICO's point.

***

In finally catching up with Douglas Rushkoff's Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, the section on cashless societies and local currencies reminded us that in the 1960s and 1970s, New Yorkers considered it acceptable to tip with subway tokens, even in the best restaurants. Who now would leave a Metro Card? Currencies may be local or national; cashlessness is global. It may be great for those who don't need to think about how much they spend, but it means all transactions are intermediated, with a percentage skimmed off the top for the middlefolk. The costs of cash have been invisible to us, as Dave Birch says, but it is public infrastructure. Cashlessness privatizes that without any debate about the social benefits or costs. How centralized will this new infrastructure become? What happens to sectors that aren't commercially valuable? When do those commissions start to rise? What power will we have to push back? Even on-the-brink Sweden is reportedly rethinking its approach for just these reasons In a survey, only 25% wanted a fully cashless society.

***

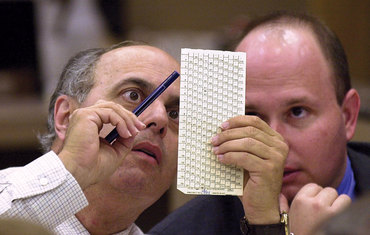

Incredibly, 18 years after chad hung and people disposed in Bush versus Gore, ballots are still being designed in ways that confuse voters, even in Broward County, which should have learned better. The Washington Post tell us that in both New York and Florida ballot designs left people confused (seeing them, we can see why). For UK voters accustomed to a bit of paper with big names and boxes to check with a stubby pencil, it's baffling. Granted, the multiple federal races, state races, local officers, judges, referendums, and propositions in an average US election make ballot design a far more complex problem. There is advice available, from the US Election Assistance Commission, which publishes design best practices, but I'm reliably told it's nonetheless difficult to do well. On Twitter, Dana Chisnell provides a series of links that taken together explain some background. Among them is this one from the Center for Civic Design, which explains why voting in the US is *hard* - and not just because of the ballots.

***

Finally, a word of advice. No matter how cool it sounds, you do not want a solar-powered, radio-controlled watch. Especially not for travel. TMOT.

Illustrations: Chad 2000.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.