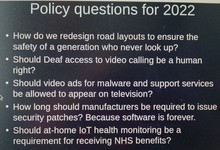

Policy questions for 2022

For last weekend's OpenTech I had recklessly suggested imagining the Daily Mail headlines of the future. Come to actually plan the talk, a broader scope seemed wiser, and after some limbering up with possible near-future headlines, which you can read on my slides, posted here, I wound up considering what might be genuine policy questions five years from now. As a way of assessing whether I had any credentials as a futurist, I referred the audience to a piece I wrote for Salon as 1998 opened, Top Ten New Jobs for 2002. (There was also a Daily Telegraph version.)

For last weekend's OpenTech I had recklessly suggested imagining the Daily Mail headlines of the future. Come to actually plan the talk, a broader scope seemed wiser, and after some limbering up with possible near-future headlines, which you can read on my slides, posted here, I wound up considering what might be genuine policy questions five years from now. As a way of assessing whether I had any credentials as a futurist, I referred the audience to a piece I wrote for Salon as 1998 opened, Top Ten New Jobs for 2002. (There was also a Daily Telegraph version.)

To score the jobs I proposed there, two we do for ourselves: people reviewer (or at least researcher) and real-time biographer. Large companies and the very wealthy have citizenship brokers (aka "tax advisors"), data obfuscators are better known as reputation managers, and embedded advertising managers are what a certain number of editors have been forced to become when the job hasn't been automated entirely. Copyright protection officers, digital actors' guild representatives, and computer therapists have yet to arise, but for "human virtual servants" we have myriad versions of mechanical Turk (see, for example, Annalee Newitz's Atlantic piece on Google raters). I haven't actually heard anyone describe themselves as an "electronic image consultant" but I can't believe they don't exist. So: not too bad a score, really.

The rest of the limbering-up portion proposed some near-future headlines, and considered extracts from the actual Class of 2020 Mindset list (issued in 2016), plus some thoughts about the 2035 Mindset list (babies born in 2017) and the 2026 list (today's nine-year-olds). You can read these for yourselves.

The policy questions all have current inspirations. These days, randomly wandering phone-neverwhered pedestrians are a constant menace, and it seems to be getting worse - in London you even see cyclists in traffic, earphones in, texting (while a similarly-equipped oblivious pedestrian vaguely strays in front of them). Road safety for this wantonly deaf-and-blind generation is an obvious conundrum, only partially solvable by initiatives like that of the German city of Augsberg, where they've embedded lights in the pavement so phone-starers will notice them.

The policy questions all have current inspirations. These days, randomly wandering phone-neverwhered pedestrians are a constant menace, and it seems to be getting worse - in London you even see cyclists in traffic, earphones in, texting (while a similarly-equipped oblivious pedestrian vaguely strays in front of them). Road safety for this wantonly deaf-and-blind generation is an obvious conundrum, only partially solvable by initiatives like that of the German city of Augsberg, where they've embedded lights in the pavement so phone-starers will notice them.

Various options occur: repurposing disused tube tunnels as segregated walkways, for example, or building an elaborate network of sensors that an app on the phone follows automatically. My favorite suggestion from a pre-conference conversation: pneumatic tubes! This is a way-underused technology.

Video ads for malware on TV are with us, at least for the YouTube generation: to its product trials and technical support the shadow malware business infrastructure has added polished marketing campaigns complete with video ads on YouTube. Cyber crime is the fastest-growing industry in the world, I was told at a security meeting recently. Given the UK's imminent need for new sources of economic growth...

The Wannacry attack has since given new weight to the question of how long manufacturers should be required to issue security patches, because software is forever. Columbia University professor Steve Bellovin more thoughtfully asks, who pays? As he writes, until we find a different answer, we all do. An audience member suggested requiring "supported-until" declarations on new hardware and software. This won't help when vendors go out of business, and won't make consumers patch big-ticket items like refrigerators and cars, but it would help us make slightly more informed decisions, especially regarding content restricted by digital rights management.

The IoT at-home health monitoring requirement in return for receiving NHS benefits seems a logical extension of then-Prime Minister David Cameron's 2011 statement that all patients should contribute their data for research; I believe he later said sharing data should be a required return for receiving NHS benefits. Deaf access to video calling seems like a no-brainer, particularly for those whose first language is signing.

An audience member suggested we may need a law to prevent the appearance in ads of synthetic versions of dead relatives. Of course you hope advertisers won't have that level of bad taste, but Facebook did mark a friend's 50th birthday with an ad for funeral arrangements featuring a bereaved female who looked disturbingly like her daughter.

Further suggestions were more along the lines of the headlines I originally promised:

- Large internet company creates its own military force. Seems all too possible.

- Alexa wins First Amendment rights. Two months ago, Arkansas police sought to compel a defendant in a murder case to grant access to the data collected by the Alexa in his home. Amazon tried to claim Alexa's replies were protected by the First Amendment, but withdrew when the suspect agreed to hand over the data. Google has also tried to claim First Amendment protection for its search results. So: not too far-fetched.

- Replacing 999 (UK emergency services; 911 in the US) requires all phone microphones to be kept on all the time. All too imaginable: I worry that within my lifetime it will become suspicious if you do not have data collection devices in your home that can be secretly accessed and reviewed by police at any time.

- The last person on a permanent employment contract retires.

Sadly, this week's election manifestos tread the same old ground. Don't they know we have a different generation's future to imagine?

Sadly, this week's election manifestos tread the same old ground. Don't they know we have a different generation's future to imagine?

Illustrations: Presenting at OpenTech (photo by Hadley Beeman); Future, 1000 meters;

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.