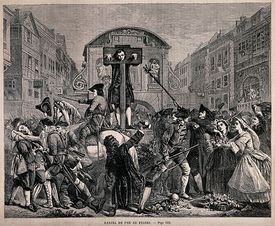

Mob rule

The journalist David Wolinsky contacted me a few weeks back to ask if we could talk about the history of how people have treated each other online for his oral history project. Sure. So, by way of limbering up...

The journalist David Wolinsky contacted me a few weeks back to ask if we could talk about the history of how people have treated each other online for his oral history project. Sure. So, by way of limbering up...

In terms of individual behavior, I'm not convinced things have changed all that much. Go back to the late 1980s, and you find Sara Kiesler writing an early study of computer-mediated communication (as it was called then) and finding that something about the distancing effect of being alone with a screen and keyboard disinhibited people from saying things they'd never say face-to-face. This turned out to be true whether or not the people communicating knew each other in real life - even if they worked in the same company. Fast forward 20 years to the 2008 Computers, Freedom, and Privacy conference, and it's a panel on online bullying and hate speech. At which the  University of Maryland professor Danielle Citron, who went on to write the recent book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, and Ann Bartow, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, told some pretty hair-raising stories. The most notable detail I remember was that often the (usually male) people dishing out the harassment posted from their clearly identifiable work addresses - the behavior was not about being anonymous. The panel concluded that you were far more likely to be bullied online by someone you knew personally. Citron's book includes several notable examples of that.

University of Maryland professor Danielle Citron, who went on to write the recent book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, and Ann Bartow, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, told some pretty hair-raising stories. The most notable detail I remember was that often the (usually male) people dishing out the harassment posted from their clearly identifiable work addresses - the behavior was not about being anonymous. The panel concluded that you were far more likely to be bullied online by someone you knew personally. Citron's book includes several notable examples of that.

Or try 1991, which net.wars revisited a couple of months ago, comparing two books of essays covering women's experiences in and with technology, then and now. Their experiences are depressingly similar, even if no one argues that graphical interfaces are "girlish" any more.

Even pack behavior has not, in some ways, changed all that much. Pick your favorite mob of today and compare and contrast with the early 1990s. Some examples. In 1992, the alt.tasteless newsgroup invaded rec.pets.cats - that is, frequent posters in one Usenet newsgroup deliberately disrupted the perfectly harmless conversations of another on a lark (this was before anyone said "for the lolz"). In 1993's A Rape in Cyberspace, one player on Lambda MOO took over other players' characters and forced them to act and speak in ways their owners felt were defamatory. No wonder Stephanie Brail called harassment "the price of admission" in 1991.

Two big things are different now: scale and speed. Venues like Lambda MOO and Usenet, as important to their participants as they were at the time, were (and are) niche communities. Wikipedia's figures, sourced from Altopia.com, indicate that Usenet traffic is still growing today, but it seems likely that's due to the use of binary newsgroups for file transfers; none of the admittedly small numbers of newsgroups I still read have anything like the number or variety of posters they did 20 years ago. Even at its peak Usenet never had anything like Facebook's billion-plus users or Twitter's 307 million. More than that, Usenet was an asynchronous medium: no matter how fast and furiously you pounded the keyboard, your message still took time to propagate - sometimes, even hours! - and so did your response. While you waited, there was nothing to do but twitch. Twitter's pervasive megaphone has the accelerants of SMS, mobile phones, and instant delivery.

The result is a different level of consequence. While it's true that in 1994, when the Church of Scientology tried to smother alt.religion.scientology to keep its most secret documents offline, the result was real police raids on real people's homes, getting to that stage took months and required legal action, court orders, and warrants. Today's social media mobs can end someone's employment in a few hours. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey sees Twitter as the most powerful microphone in the world ; does that also mean the most powerful bully pulpit in the world? Because so much on Twitter is public, it feeds and feeds back upon major media outlets, for both bad and good.

The hardest argument to make to anyone caught up in what used to be known as "flame wars" is to take time to think. Under pressure of tweets and "mentions", even smart, sensible people become insistent that a response must be made *right now*, instantly, urgently, fearing they may lose control of "the story". The reality is that if you think there is that much urgency you have *already* lost control of the story, not least because you've lost control of yourself.

I had a weird habit of reading etiquette books as a child: all those books of rules about who has to stand up when someone enters a room and how long you could take to send a thank-you note. I've spent most of my life since ignoring them all. But one that has always stuck in my mind was the advice that after writing an angry (postal!) letter you should set it aside for three days before rereading it to see if you still thought it was a good idea to send it. It's still good advice, but try getting anyone to take it.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.