Signaled

A while back, I was trying to get a friend to install the encrypted messaging app Signal.

A while back, I was trying to get a friend to install the encrypted messaging app Signal.

"Oh, I don't want another messaging app."

Well, I said, it's not *another* messaging app. Use it to replace the app you currently use for texting (SMS) and it will just sit there showing you your text messages. But whenever you encounter another Signal user those messages will be encrypted. People sometimes accepted this; more often, they wanted to know why I couldn't just use WhatsApp, like their school group, tennis club, other friends... (Well, see, it may be encrypted, but it's still owned by the Facebook currently known as Meta.)

This week I learned that soon I won't be able to make this argument any more, because...Signal will be dropping SMS support for Android users sometime in the next few months. I don't love either the plan or the vagueness of its timing. (For reasons I don't entirely understand, this doesn't apply to the nether world of iPhone users.)

The company's blog posting lists several reasons. Apparently the app's SMS integration is confusing to many users, who are unclear about when their messages are encrypted and when they're not. Whether this is true is being disputed in the related forum thread discussing this decision. On the bah! side is "even my grandmother can use it" (snarl) and on the other the valid evidence of the many questions users have posted about this over the years in the support forums. Maybe solvable with some user interface tweaks?

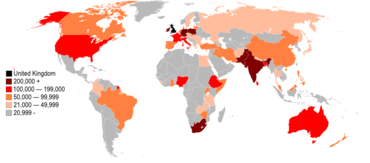

Second, the pricing differential between texting and Signal messages, which transit the Internet as data, has reversed since Signal began. Where data plans used to be rare and expensive, and SMS texts cheap or bundled with phone service, today data plans are common, and SMS has become expensive in some parts of the world. There, the confusion between SMS and Signal messaging really matters. I can't argue with that except to note that equally it's a problem that does *not* apply in many countries. Again, perhaps solvable with user settings...but it's fair enough to say that supporting this may not be the best use of Signal's limited resources. I don't have insight into the distribution of Signal's global user base, and users in other countries are likely to be facing bigger risks than I am.

Third is sort of a purity argument: it's inherently contradictory to include an insecure protocol in an app intended to protect security and privacy. "Inconsistent with our values." The forum discussion is split on this. While many agree with this position, many of the rest of us live in a world that includes lots of people who do not use, and do not want to use (see above), Signal, and it is vastly more convenient to have a single messaging app that handles both.

Signal may not like to stress this aspect, but one problem with trusting an encrypted messaging app in the first place is that the privacy and security are only as good as your correspondents' intentions. Maybe all your contacts set their messages to disappear after a week, password-protect and encrypt their message database, and assign every contact an alias. Or, maybe they don't password-protect anything, never delete anything, and mirror the device to three other computers, all of which they leave lying around in public. You cannot know for sure. So a certain level of insecurity is baked into the most secure installations no matter what you do. I don't see SMS as the biggest problem here.

I think this decision is going to pose real, practical problems for Signal in terms of retaining and growing its user base; it surely does not want the app's presence on a phone become governments' watch-this-person flag. At least in Western countries, SMS is inescapable. It would be better if two-factor authentication used a less hackable alternative, but at the moment SMS is the widespread vector of corporate choice. We consumers don't actually get to choose to dump it until they do. A switch is apparently happening very slowly behind the scenes in the form of RCS, which I don't even know if my aged phone supports. In the meantime, Signal becomes the "another messaging app" we began with - and historically, diminished convenience has been one of the biggest blocks to widespread adoption of privacy-enhancing technologies.

Signal's decision raises the possibility that we are heading into a time where texting people becomes far more difficult. It may become like the early days, when you could only text people using the same phone company as you - for example, Apple has yet to adopt RCS. Every new contact will have to start with a negotiation by email or phone: how do I text you? In *addition* to everything else.

The Internet isn't splintering (yet); email may be despised, but every service remains interoperable. But the mobile world looks like breaking into silos. I have family members who don't understand why they can't send me iMessages or FaceTime me (no iPhone?), and friends I can't message unless I want to adopt WhatsApp or Telegram (groan - another messaging app?).

Signal may well be right that this move is a win for security, privacy, and user clarity. But for communication? In *this* house, it's a frustrating regression.

Illustrations: Midjourney's rendering of "railway signal tracks crossing",

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

One of the large, ignored problems of cybersecurity is that every site, every supplier, ever software coder, every hardware manufacturer makes decisions as if theirs were the only rules you ever have to observe.

One of the large, ignored problems of cybersecurity is that every site, every supplier, ever software coder, every hardware manufacturer makes decisions as if theirs were the only rules you ever have to observe.

_31-thumb-370x228-1144.jpg)

-thumb-370x277-1083.jpg)

_in_Luxembourg_with_flags-thumb-370x277-576.jpg) We rarely talk about it this way, but sometimes what makes a computer secure is a matter of perspective. Two weeks ago, at the

We rarely talk about it this way, but sometimes what makes a computer secure is a matter of perspective. Two weeks ago, at the

As if cued by the end of

As if cued by the end of

It's a sign of the times that the most immediately useful explanation of the

It's a sign of the times that the most immediately useful explanation of the  So here is this week's killer question: "Are you aware of any large-scale systems employing this protection?"

So here is this week's killer question: "Are you aware of any large-scale systems employing this protection?" Well, here we are in 2017, and biometrics are more widely used, even though not as widely deployed as they might have hoped in 1999. (There are good reasons for this, as

Well, here we are in 2017, and biometrics are more widely used, even though not as widely deployed as they might have hoped in 1999. (There are good reasons for this, as  This week, at the European Association for Biometrics held a

This week, at the European Association for Biometrics held a  There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones,

There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones,  The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article

The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article

It was Farrell's comment, though, that sparked the realization that fake news cannot be solved by thinking of it as a problem in only one of the fields of journalism, international relations, economic inequality, market forces, or technology. It is all those things and more, and we will not make any progress until we take an approach that combines all those disciplines.

It was Farrell's comment, though, that sparked the realization that fake news cannot be solved by thinking of it as a problem in only one of the fields of journalism, international relations, economic inequality, market forces, or technology. It is all those things and more, and we will not make any progress until we take an approach that combines all those disciplines.