The zero on the phone

Among the minor casualties of the pandemic has been the appearance of a Swiss prototype robot at this year's We Robot, the ninth year of this unique conference that crosses engineering, technology policy, and law to identify future conflicts and pre-emptively suggest solutions. The result was to leave the robots considered by this virtual We Robot remarkably (appropriately) abstract.

Among the minor casualties of the pandemic has been the appearance of a Swiss prototype robot at this year's We Robot, the ninth year of this unique conference that crosses engineering, technology policy, and law to identify future conflicts and pre-emptively suggest solutions. The result was to leave the robots considered by this virtual We Robot remarkably (appropriately) abstract.

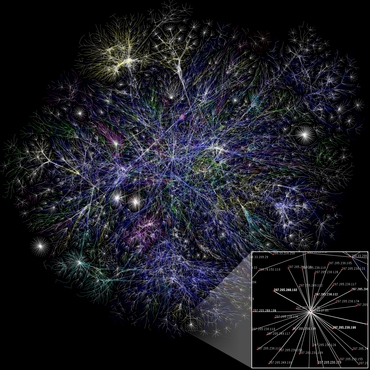

We Robot was founded to get a jump on the coming conflicts that robots will bring to law and policy, in part so that we don't repeat the Internet experience of repeating the same arguments decades on end. This year's event pre-empted the Internet experience in a new way: many authors have drawn on the failed optimism and cooperation of the 1990s to begin defining ways to ensure that robotics and AI do not follow the same path. Where at the beginning we were all eager to embrace robots, this year their disembodied AIs are being done *to* us.

In the one slight exception to this rule, Hallie Siegel's exploration of senior citizens' attitudes towards new technologies found that the seniors she studies are pragmatic, concerned about their privacy and autonomy and only really interested in technologies that provided benefits they really need.

Jason Millar and Elizabeth Gray drew directly on the Internet experience by comparing network neutrality to the issues surrounding the mapping software that controls turn-by-turn navigation systems in a discussion of "mobility shaping". Should navigation services be common carriers, as telephone lines are? The idea appeals to me, if only because the potential for physical control of where our vehicles are allowed to go seems so clear.

The theme of exploitation was particularly visible in the two papers on Africa. In the first, Arthur Gwagwa (Strathmore University, Nairobi), Erika Kraemer-Mbula, Nagla Rizk, Isaac Rutenberg, and Jeremy de Beer warn that the combination of foreign capital and local resources is likely to reproduce the power structures of previous forms of colonialism, an argument also seen recently in a paper by Abeba Birhane. Women in particular, who run the majority of start-ups in some African countries, may be ignored, and the authors suggest that a GDPR-like rule awarding individuals control over their own data could be crucial in creating value for, rather than extracted from, Africa.

In the second, Laura Foster (Indiana University), Bram Van Wiele, and Tobias Schönwetter extracted a database of press stories about AI in Africa from Lexis-Nexus, to find the familiar set of claims for new technology: happy, value-neutral disruption, yay!. The failure of most of these articles to consider gender and race, they observed, doesn't make the emerging picture neutral, but serves to reinforce the default of the straight, white male.

One way we push back against AI/robot control is the "human in the loop" to whom the final decision is delegated. This human has featured in every We Robot conference, most notably in 2016 as Madeleine Elish's moral crumple zone. In his paper, Liam McCoy argues for the importance of meaningful control, because the middle ground, where the human is expected to solve the most complex situations where AI fails without support or authority is truly dangerous. The middle ground may be profitable; at UK IGF a few weeks ago, Gus Hosein noted that automating dispute resolution has what's made GAFA rich. But in the higher stakes of cyber-physical systems, the human you summon by pushing zero has to be able to make a difference.

Silvia de Conca's idea of "human-centered legal design", which sought to give autonomous agents a duty of care as a way of filling the gap in liability that presently exists, and Cynthia Khoo's interest in vulnerable communities who are harmed by behavior that emerges from combined business models, platform scale, human nature, and algorithm design presented different methods of putting a human in the loop. Often, Khoo has found in investigating this idea, the potential harm was in fact known and simply ignored; how much can and should be foreseen when system parts interact in unexpected ways is a rising issue.

Several papers explored previously unnoticed vectors for bias and control. Sentiment analysis, last seen being called "the snake oil of 2011", and its successor, emotion analysis, which I first saw explored in the 1990s by Rosalind Picard at MIT, are creeping into AI systems. Some are particularly dubious: aggression detection systems and emotion recognition cameras.

Emily McBain-Ashfield and Jason Millar are the first I'm aware of to study how stereotyping gets into these systems. Yes, it's in the data - but the problem lies in the process analyzing and tagging it. The authors found three methods of doing this: manual (human, slow), dictionary-based using seed words (automated), and crowdsourced (see also Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri's 2019 book, Ghost Work. All have problems; automating that sort of issue creates notoriously crude mistakes, and the participants in crowdsourcing may be from very different linguistic and cultural contexts.

The discussant for this paper, Osonde Osaba sounded appalled: "By having these AI models of emotion out in the wild in commercial products we are essentially sanctioning the unregulated experimentation on humans and their emotional processes without oversight or control."

Remedies have to contend, however, with the legacy infrastructure. Alice Xiang discovered a conflict between traditional anti-discrimination law, which bars decision making based on a set of protected classes and the technical methods of mitigating algorithmic bias. "If we're not careful," she said, "the vast majority of approaches proposed in machine learning literature might actually be illegal if they are ever tested in court."

We Robot 2020 was the first to be held outside the US, and chairs Florian Martin-Bariteau, Jason Millar, and Katie Szilagyi set out to widen its international character and diversity. When the pandemic hit, the resulting exceptional breadth of location of authors and discussants made it infeasible to ask everyone to pretend they were in Ottawa's time zone. The conference therefore has recorded the authors' and discussants' conversations as if live - which means that you, too, can experience the originals. Just follow the links. We Robot events not already linked here: 2013; 2015; 2016 workshop; 2017; 2018 workshop and conference; 2019 workshop and conference.

Illustrations: Our robot avatars attend the conference for us on the We Robot 2020 poster.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.