New masters

The late, great film critic Roger Ebert argued in April 2010 that games could never be art on the level of the great poets, composers, and filmmakers, a position he modified a few months later after nearly 4,500 comments convinced him he hadn't played enough games to have an informed opinion. I suspect he was showing his age a little: it's always easy to dismiss the new medium you didn't grow up with In their time, as some of Ebert's commenters argued, movies had to prove their quality, too - and many people are only just recognizing that TV is in a golden age of drama that means it, too, can no longer be sneered at just because it's television. Granted, a game can take a long time to play through - but so can Wagner's Ring der Niebelungen.

The late, great film critic Roger Ebert argued in April 2010 that games could never be art on the level of the great poets, composers, and filmmakers, a position he modified a few months later after nearly 4,500 comments convinced him he hadn't played enough games to have an informed opinion. I suspect he was showing his age a little: it's always easy to dismiss the new medium you didn't grow up with In their time, as some of Ebert's commenters argued, movies had to prove their quality, too - and many people are only just recognizing that TV is in a golden age of drama that means it, too, can no longer be sneered at just because it's television. Granted, a game can take a long time to play through - but so can Wagner's Ring der Niebelungen.

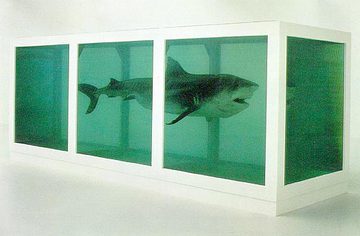

Of course, there's no reason games have to be art; no one expects that of tennis or football, even when a few individual players are spoken of as "artists". But what was notable at this week's IGGI Symposium was the number of areas in which games researchers are exploring what seem like analogues for known storytelling techniques that have been developed over millennia in (other) art forms. If a shark floating in a tank of formaldehyde can be art, why not a game?

"The exciting things in science happen when science meets the arts," one of IGGI's supervising professors said on Thursday by way of sending everyone back to work.

When I brought up Ebert's argument,Tom Cole, who is studying using the features specific to computer games to evoke emotion, commented that art is only recognized later, after time has passed. Fair point. Even so, in presenting his work, Cole noted that, "People read books and watch films, and it changes them, but it doesn't happen so much with games." Since games do evoke emotion - if only frustration - what is different?

Cole was one of several dozen PhD students showing off their work at this week's symposium. IGGI stands for "Intelligent Games and Game Intelligence", and is a sprawling PhD program including three universities (York, Essex, and Goldsmiths) and some 60 other partners. Some of their presentations would fit right in at any AI conference, a fact simply explained by Richard Bartle, who wrote the early 1980s multiplayer online game MUD.

"Games and AI are particularly compatible," he said, "because games have opponents who are intelligent, and games give AI something to be intelligent about in a controlled environment." In his own early experience, "I added AI so I could make the non-player characters more intelligent. Then they were too smart for the players and I had to dumb them down." So the two have gone hand in hand since the beginning; the talk given by DeepMind's Tom Schaur on the use of convolutional neural networks to design the company's Go champion fits in either type of conference.

"Games and AI are particularly compatible," he said, "because games have opponents who are intelligent, and games give AI something to be intelligent about in a controlled environment." In his own early experience, "I added AI so I could make the non-player characters more intelligent. Then they were too smart for the players and I had to dumb them down." So the two have gone hand in hand since the beginning; the talk given by DeepMind's Tom Schaur on the use of convolutional neural networks to design the company's Go champion fits in either type of conference.

UC Santa Cruz professor Michael Mateas, perhaps best known for Facade, has been working on auto-generated games for a decade or more, partly with the goal of "opening up the game space to those who couldn't otherwise make them".

You can see his point. The possibility exists that if games are not art now, it could be because of the technical complexity of the tools needed to make them. We are only at the beginning of game and story generators (something PhD student Emily Marriott is also working on), developing interactive narratives (discussed at length by Emily Short), and complex structures. We needed (and still need) computational power, for both developers and players, and bandwidth, and on top of that tools that artists who are not programmers can use. The technical barriers between artist and output are still high, compared to writing, painting, sculpture, music, and film, because you need so many different skills; but all these aspects are being worked on.

While writing this, I've been reminded that it's not that long - 40 years or so - since it was considered questionable whether science fiction could be art. In the early 1970s, I recall reading an essay by Ursula K. Leguin that argued the "for" case. Discarding a load of characters and pulp plots from previous decades, she described her encounter with the character she believed was the first truly fully rounded character in the genre. Step forward, Frodo Baggins.

However, the "is it art?" question isn't a fair representation of IGGI's work. It's particularly notable that two of the PhD students are focusing on entirely non-traditional uses of games: Jen Beeston (York) is looking at using games to improve wellbeing in neurological care homes, while Janet Gibbs (Goldsmiths) is working on how to create interfaces that simulate various senses. Her first interest is to create games that work for deaf and blind people, but she's also interested in simulating novel senses: magnetic direction, for example, and echolocation.

All of this points to a far more varied future than we typically realize. In future the question may not be whether the thing you're pointing to is art - but whether it's a game.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.