Nine meals from anarchy*

The untutored, asked how to handle a food crisis, are prone to suggest that everyone grow vegetables in their backyards. They did it in World War II!

The untutored, asked how to handle a food crisis, are prone to suggest that everyone grow vegetables in their backyards. They did it in World War II!

I fell into this trap once myself, during the 2008 financial crisis, when I heard a Russian commentator explain on US talk radio that Americans could never survive because we were too soft and individualistic, whereas Russians were used to helping each other out in hard times, living together in cramped conditions, and working around shortages. Nonsense, I thought. Americans are quite capable of turning off their TVs, getting up off their couches, and doing useful stuff when they need to. Wishing for a Plan B, I thought of the huge backyard some Pennsylvania friends had, which backed onto three more similarly-sized backyards, and imagined a cooperative arrangement in which one family kept chickens and another grew some things, and a third grew some complementary things...and they swapped and so on.

My Pennsylvania friends were not impressed. "Is this a joke?"

"It's a Plan B! It's good to have a Plan B!"

It's not a Plan B.

A couple of years ago, at the annual conference convened by the Cybernetics Society, I learned it wasn't even a Plan Y.

"It's subsistence farming," Kate Cooper explained as part of her talk on food security. The grueling full-time unpredictability of that is is what most of us gave up in favor of selecting items off grocery store shelves once or twice a week.

The point about subsistence farming is that it's highly unreliable, highly individual, and doesn't scale to the levels required for a modern society, still less for a densely populated modern British society that imports almost all its food. Yes, people were encouraged to grow vegetables in World War II, but although the net effect was good for morale and for helping people better understand the foods they eat, it doesn't help anyone understand the food system and its scale and complexity. Basically, in terms of the problem of feeding the nation, it was a rounding error. Worth doing, but not a solution.

Cooper is the executive director of the Birmingham Food Council, a community interest company that grew out of efforts to think about the future of Birmingham. "It's our job to be an exemplar of how to think about the food system," she explained.

Two years later, with stories everywhere about escalating food prices and dangerous shortages, the interdependencies that underlie our food supply are being exposed by the intermingling of three separate crises, each of which would be bad on its own: the pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and climate change. A source I can't recall calls this constellation a "polycrisis" - multiple simultaneous crises that interact to make them all worse. Plus, while the present government doesn't admit it, *Brexit* has added substantially to the challenges of maintaining the UK's increasingly brittle, highly complex system that few of us understand by fracturing trade relationships and pushing workers out of the industry.

As part of its research, the Council created The Game, a scenario-based role-playing game for decision makers, food sector leaders, researchers, and other policy influencers in which teams of four to six are put in charge of a city and must maintain the residents' access to enough safe and nutritious food.

I felt better about my own level of ignorance when I learned that one player's idea for combating shortages was to grow potatoes along the A38, a major route that runs from Bodmin, Cornwall, to Mansfield, Nottinghamshire. No idea of scale, you see, or the toxins passing automobiles deposit in the soil. (To say nothing of the inefficiencies of trying to farm a plot of land that's 292 miles long and a few hundred yards wide...) Another player wanted to get the national government to send in the army. Also not helping...but they were not alone, as many players found it difficult to feed their populations. People who had played it when the pandemic began forcing lockdowns and hourly changes to the food system. "Nothing had surprised [the people who had played The Game]", she said. Even so, the lockdowns showed the fragility of the food system and how powerless local officials are to do anything about it.

There are options at the national level. If you are lucky enough to have a government that has both the resources and the will to plan for the future, you can create buffer stocks to tide you through a crisis. You need a plan to rotate and resupply since some things (grain) store much better than others (fresh produce). Cooper has a simple plan for deciding which foodstuffs should be stored and which not: is it subject to VAT? That would lead to storing essentials - the healthy, nutritious stuff - and not candy, alcohol, caffeine, sugar, potato chips. Cooper calls those "drug foods", and notes that over 50% of most household budgets are spent on them, 6% of the potato crop goes to making Walker's potato chips, and a 2012 estimate found that Coca Cola's global consumption of water was enough to meet the annual daily needs of more than 2 billion people.

"Is this a sensible use of increasingly scarce land and water?" she asked.

Put like that, what can you say?

Illustrations: Kate Cooper. *Quote attributed to Alfred Henry Lewis, 1906.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

-thumb-370x369-968.jpg) "One case!" railed a computer industry-adjacent US libertarian on his mailing list recently. He was scathing about the authoritarianism he thought implicit in prime minister

"One case!" railed a computer industry-adjacent US libertarian on his mailing list recently. He was scathing about the authoritarianism he thought implicit in prime minister

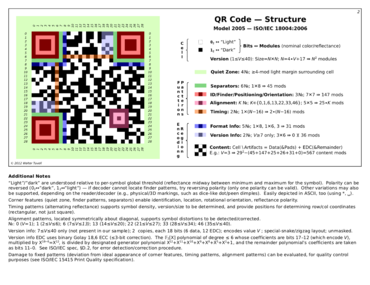

The slight reopening of international travel - at least inbound to the UK - is reupping discussions of vaccination passports, which we last

The slight reopening of international travel - at least inbound to the UK - is reupping discussions of vaccination passports, which we last

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...

With so much insecurity and mounting crisis, there's no time now to think about a lot of things that will matter later. But someday there will be. And at that time...