Well may the bogeyman come

It's only an accident of covid that this year's Computers, Privacy, and Data Protection conference - delayed from late January - coincided with the fourth anniversary of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation. Yet its failures and frustrations were on everyone's mind as they considered new legislation forthcoming from the EU: the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, and, especially, the AI Act,

It's only an accident of covid that this year's Computers, Privacy, and Data Protection conference - delayed from late January - coincided with the fourth anniversary of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation. Yet its failures and frustrations were on everyone's mind as they considered new legislation forthcoming from the EU: the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, and, especially, the AI Act,

Two main frustrations: despite GDPR, privacy invasions continue to expand, and, related, enforcement has been extremely limited. The first is obvious to everyone here. For the second...as Max Schrems explained in a panel on GDPR enforcement, none of the cross-border cases his NGO, noyb, filed on May 19, 2018, the day after GDPR came into force, have been decided, and even decisions on simpler cases have failed to deal with broader questions.

In one of his examples, Spain rejected a complaint because it wasn't doing historic cases and Austria claimed the case was solved because the organization involved had changed its procedures. "But my rights were violated then." There was no redress.

Schrems is the data protection bogeyman; because legal actions he has brought have twice struck down US-EU agreements to enable data flows, the possibility of "Schrems III" if the next version gets it wrong is frequently mentioned. This particular panel highlighted numerous barriers that block effective action.

Other speakers highlighted numerous gaps between countries that impede cross-border complaints: some authorities have tight deadlines that expire while other authorities are working to more leisurely schedules; there are many conflicts between national procedural laws; each data protection authority has its own approach and requirements; and every cross-border complaint must be time-consumingly translated into English, even when both relevant authorities speak, say, German. "Getting an answer to a two-minute question takes four months," Nina Herbort said, highlighting the common underlying problem: underresourcing.

"Weren't they designed to fail?" Finn Myrstad asked.

Even successful enforcement has largely been limited to levying fines - and despite some of the eye-watering numbers they're still just cost of doing business to major technology platforms.

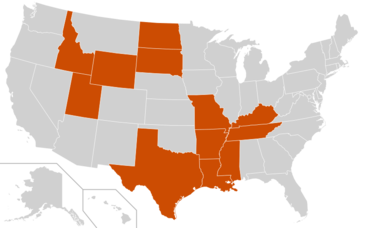

"We have the tools for structural sanctions," Johnny Ryan said in a discussion on judicial actions. Some of that is beginning to happen. A day earlier, the UK'a Information Commissioner's Office fined Clearview AI £7.5 million and ordered it to delete the images it holds of UK residents. In February, Canada issued a similar order; a few weeks ago, Illinois permanently banned the company from selling its database to most private actors and businesses nationwide, and barred it from selling its service to any entity within Illinois for five years. Sanctions like these hurt more than fines as does requiring companies to delete the algorithms they've based on illegally acquired data.

Other suggestions included building sovereignty by ensuring that public procurement does not default to off-the-shelf products from a few foreign companies but is built on local expertise, advocated by. Jan-Philipp Albrecht, the former MEP who panel on the impact of Schrems II that he is now building up cloud providers using locally-built hardware and open source software for the province of Schleswig-Holstein. Quang-Minh Lepescheux suggested requiring transparency in how people are trained to use automated decision making systems and forcing technology providers to accept third-party testing. Cristina Caffara, probably the only antitrust lawyer in sight, wants privacy advocates and antitrust lawyers to work together; the economists inside competition authorities insist that more data means better products so it's good for consumers. Rebecca Slaughter wants to give companies the clarity they say they want (until they get it): clear, regularly updated rules banning a list of practices with a catchall. Ryan also noted that some sanctions can vastly improve enforcement efficiency: there's nothing to investigate after banning a company from making acquisitions. Enforcing purpose limitation and banning the single "OK to everything" is more complicated but, "Purpose limitation is Kryptonite to Big Tech when it's misusing data."

Any and all of these are valuable. But new kinds of thinking are also needed. The more complex issue and another major theme was the limitations of focusing on personal data and individual rights. This was long predicted as a particular problem for genetic data - the former science journalist Tom Wilkie was first to point out the implications, sounding a warning in his book Perilous Knowledge, published in 1994, at the beginning of the Human Genome Project. Singling out individuals who have been harmed can easily obfuscate collective damage. The obvious example is Cambridge Analytica and Facebook; the damage to national elections can't be captured one Friends list at a time, controls on the increasing use of aggregated data require protection at scale, and, perversely, monitoring for bias and discrimination requires data collection.

In response to a panel on harmful patterns in recent privacy proposals, an audience member suggested that the African philosophy of ubuntu as a useful source of ideas for thinking about collective and, even more important, *interdependent* data. This is where we need to go. Many forms of data - including both genetic data and financial data - cannot be thought of any other way.

Illustrations: The Norwegian Consumer Council receives EPIC's International Privacy Champion award at CPDP 2022.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

A few weeks ago,

A few weeks ago,