The abundance of countries

First up is the Court of Justice of the European Union's ruling largely upholding Article 17 of the 2019 Copyright Directive. Article 17, also known as the "upload filter", was last seen leading many to predict it would break the web. Poland challenged the provision, arguing that requiring platforms to check user-provided material for legality infringed the rights to freedom of expression and information.

CJEU dismissed Poland's complaint, and Article 17 stands. However, at a panel convened by Communia, former Pirate Party MEP Felix Reda found the disappointment is outweighed by the court's opinion regarding safeguards, which bans general monitoring, and, Joao Pedro Quantais explained, restrict content removal to material whose infringing nature is obvious.

More than half of EU countries have failed to meet the June 2021 deadline to transpose the directive into national law, and some that have simply copied and pasted the directive's two most contentious articles - Articles 17 and 15 (the "link tax") rather than attempt to resolve the directive's internal contradictions. As Glyn Moody explains at Walled Culture, the directive requires the platforms to both block copyright-infringing content from being uploaded and make sure legal content is not removed. Moody also reports that Finland's attempts at resolution have attracted complaints from the copyright industries, who want the country to make its law more restrictive. Among the other countries that have transposed the directive, Reda believes only Germany's and Austria's interpretations provide safeguards in line with the court's ruling - and Austria's only with some changes.

***

The best response I've seen to the potential sale of Twitter comes from writer Racheline Maltese: who tweeted, "On the Internet, your home will always leave you."

In a discussion sparked by the news, Twitter user Yishan argues that "free speech" isn't what it used to be. In the 1990s version, the threat model was religious conservatives in the US. This isn't entirely true; some feminist groups also sought to censor pornography, and 1980s Internet users had to bypass Usenet hierarchy administrators to create newsgroups for sex and drugs. However, the understanding that abuse and trolling drive people away and chill them into silence definitely took longer to accept as a denial of free speech rights. Today, Yishan writes, *everyone* feels their free speech is under threat from everyone else. And they're likely right.

***

It's also worth noting the early stages of the cybercrime treaty. It's now 20 years since the Convention on Cybercrime was formulated; as of December 2020 65 states have ratified it and four have signed it. The push for a new treaty is coming from countries that either opposed the original or weren't involved in drafting it - Russia in particular, ironically enough. At Human Rights Watch, Deborah Brown warns of risks to fundamental rights: "cybercrime" has no agreed definition and some states want expansion to include "incitement to terrorism" and copyright infringement. In addition, while many states back including human rights protections, detail is lacking. However, we might get some clues from this week's White House declaration for the future of the Internet, which seeks to "reclaim the promise of the Internet" and embed human rights. It's backed by 60 countries - but not China or Russia.

There is general agreement that the vast escalation of cybercrime means better cross-border cooperation is needed, as Summer Walker writes at Foreign Policy. However, she notes that as work progressed in 2021 a number of states already felt excluded from the decision-making process.

The goal is to complete an agreement by early 2024.

***

Finally....20 years ago I wrote (in a piece from the lostweb) about the new opportunities for plagiarism afforded by the Internet. That led to a new industry sector: online services that check each new paper against a database of known material. The services do manage to find previously published text; six days after publication even a free example service rates the first two paragraphs of last week's net.wars as "100% plagiarized". Even so, the concept is flawed, particularly for academics, whose papers have been flagged or rejected for citations, standardized descriptions of experimental methodology, or reused passages describing their own previous work - "self-plagiarism". In some cases, academics have reported on Twitter, the automated systems in use at some journals reject their work before an editor can see it.

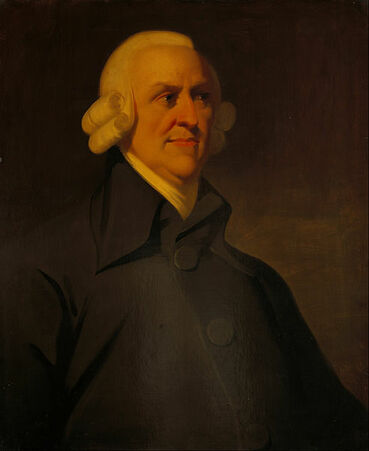

Now there's a new twist in this little arms race: rephrasing services that freshen up published material so it will pass muster. The only problem is (of course) that the AI is supremely stupid and poorly educated. Last year, Nature reported on "tortured phrases" that indicated plagiarized research papers, particularly rife in computer science. This week Essex senior lecturer Matt Lodder reported on Twitter his sightings of AI-rephrased material in students' submissions. First clue: "It read oddly." Well, yes. When I ran last week's posting through several of these services, they altered direct quotes (bad journalism), rewrote active sentences into passive ones (bad writing), and changed the meaning (bad editing). In Lodder's student's text, the AI had substituted "graph" for "chart"; in a paper submitted to a friend of his, "the separation of powers" had been rendered as "the sundering of puissances" and Adam Smith's classic had become "The Abundance of Countries". People: when you plagiarize, read what you turn in!

Illustrations: Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations (portrait from the National Gallery of Scotland, via Wikimedia).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

-thumb-370x246-1154.jpg)