The Amazing

"It's my birthday tomorrow," I said to my friend Bill Steele in early 1982. "Let's do something new and different."

"I can't," he said. "I have to go to this lecture-demonstration on psychic surgery." He was writing about it for one of Cornell's publications.

"That sounds new and different. Can I come?"

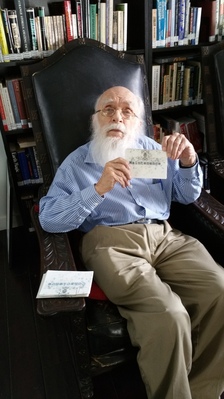

The lecturer-demonstrator was, of course, the paranormal investigator James "The Amazing" Randi, who died Wednesday. He was 92, and had survived cancer, bypass surgery, and a stroke, but it still seems unbelievable that his enormous energy and enduring curiosity could be permanently quieted. That first sighting had probably 1,000 people packed into Cornell's Stadtler auditorium; the last time I saw him, in 2016, he was telling debunking stories to a tiny group of Florida skeptics near his home, both with equal enthusiasm.

His curiosity was endless and comprehensive, even mid-controversy on climate change. Do these two differently-shaped glasses hold the same volume of liquid? Why did his refrigerator light stay off every Saturday? (Answer.)

Countless people say that seeing Randi speak launched them into skepticism. I was certainly one of them; Randi permanently altered parts of how I see the world. Just at a quick glance: Chris French, Richard Wiseman, Edzard Ernst, and Penn Jillette.

Martin Gardner's presence among the founders of the Committee for Scientific Inquiry that validated them for me, Randi was skepticism's secret sauce, upending claims so you could see their fatal flaws and offering openings for "citizen science" long before it was fashionable. One of his most important lessons was the importance of a background in deception when approaching paranormal claims. "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof," he often said, and he proved over and over that scientists have trouble doubting "extraordinary" when it's shown to them in their own lab, where they think they're in charge and where their test tubes do not lie to them. In 1987, he teamed up with Nature editor John Maddox to examine an apparently successful homeopathy experiment.

Martin Gardner's presence among the founders of the Committee for Scientific Inquiry that validated them for me, Randi was skepticism's secret sauce, upending claims so you could see their fatal flaws and offering openings for "citizen science" long before it was fashionable. One of his most important lessons was the importance of a background in deception when approaching paranormal claims. "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof," he often said, and he proved over and over that scientists have trouble doubting "extraordinary" when it's shown to them in their own lab, where they think they're in charge and where their test tubes do not lie to them. In 1987, he teamed up with Nature editor John Maddox to examine an apparently successful homeopathy experiment.

Most of us skeptics didn't meet Randi until long after his exploits as an escape artist made him famous. Every so often, though, I'd get a sense of his earlier life building his career. In one story I remember, a magician friend touring on a shoestring (so like the folk scene) would call himself at his agent's number person-to-person collect to get his itinerary. The agent would answer with something like, "He's not here, but you can reach him at the

One of those reminiscences taught me that I probably encountered Randi much earlier than I'd realized. As an insomniac teenager in the late 1960s, I used to listen to the radio - Long John Nebel's overnight talk show on New York's WOR. Randi was a frequent caller, though the only guest I really know I heard is the folksinger Michael Cooney.

I also remember Randi saying he got on Johnny Carson so often because he'd call up around when they'd be trying to fill the show with a suggestion like, "How would you like to freeze me in a block of ice?" Carson's own background in magic made him insistent that anyone claiming psychic powers on his show had better be genuine, a principle Randi was happy to help with, as Uri Geller discovered. Challenging Geller, who for a time was the world's most famous psychic, became something of an obsession for Randi - and another book, The Truth About Uri Geller.

One of his most stunning Carson appearances was his 1986 expose of televangelist faith healer Peter Popoff - also later a book, The Faith Healers. Popoff claimed that God spoke to him, directing him to call out specific audience members, their addresses, and their ailments. Randi enlisted Alexander Jason to find the radio frequency Popoff's wife was using from off-stage to feed those details, which she collected in pre-show chats, into his earpiece. That year he won a MacArthur award.

Every skeptic has their own motivations. Randi was driven both by a general love of truth and by a specific fury at seeing people cheated, deceived, and defrauded. The Popoff demonstration was great entertainment - but Popoff's operation was deadly, in that at the end of each show there would be a huge bag of life-saving medications to dispose of after Popoff told his audience to throw them away. Randi's long-time challenge - first $1,000, then $10,000, finally $1 million - to anyone who could demonstrate paranormal abilities under proper observing conditions - drew many hopefuls but no winners.

If the many obits are the first time you've encountered Randi, I'd suggest you start by reading Flim-Flam!. The James Randi Foundation has a YouTube channel with many videos showing off different aspects of his and others' work. And the 2014 documentary An Honest Liar gives a full and entertaining account of his life.

As the news broke, the science writer Charles Arthur quipped on Twitter, "The worst part is that now he can't haunt Uri Geller, because he didn't believe in ghosts." True. Even Randi has his limits. Had. Damn it. But it turned out, even there he had a plan.

Illustrations: James Randi's home library (there's a hidden skeleton behind the glass case); Randi in his library in 2016 showing off a trick he'd invented.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.