The ad delusion

The fundamental lie underlying the advertising industry is that people can be made to like ads. People inside the industry sometimes believe this to a delusional degree - at an event some years ago, for example, I remember a Facebook representative suggesting that correctly targeted ads could be even more compelling to the site's users than *pictures of their grandchildren*. As if.

The fundamental lie underlying the advertising industry is that people can be made to like ads. People inside the industry sometimes believe this to a delusional degree - at an event some years ago, for example, I remember a Facebook representative suggesting that correctly targeted ads could be even more compelling to the site's users than *pictures of their grandchildren*. As if.

Apple's design change last year to bar apps from tracking its users unless said users specifically opted in has shown the reality of this. As of April 2022, only 25% have opted in. Meanwhile, Meta estimates that this decision cost it $10 billion in revenues in 2022.

Fair to remember, though, that Apple itself still appears to track users, however, and the company is facing two class action suits after Gizmodo showed that Apple goes on tracking users even when their privacy settings are set to disable tracking completely.

This week, Ireland's Data Protection Commissioner issued Meta with a fine of €390 million and a ruling, forced on it by the European Data Protection Board, to the effect that the company cannot claim that requiring users to agree to its lengthy terms and conditions and including a clause allowing it to serve ads based on their personal data constitutes a "contract". The DPC, which wanted to rule in Meta's favor, is apparently appealing this ruling, but it's consistent with what most of us perceive to be a core principle of the General Data Protection Regulation - that is, that companies can't claim consent as a legal basis for using personal data if users haven't actively and specifically opted in.

This principle matters because of the crucial importance of defaults. As research has repeatedly shown, as many as 95% of users never change the default settings in the software and devices they use. Tech companies know and exploit this.

Meta has three months to bring its data processing operations into compliance. Its "data processing operations" are, of course, better known as Facebook, Instagram, and (presumably) WhatsApp. As a friend has often observed, how much less appealing they would sound if Meta called them that rather than use their names, and accurately described "adding a friend" as "adding a link in the database".

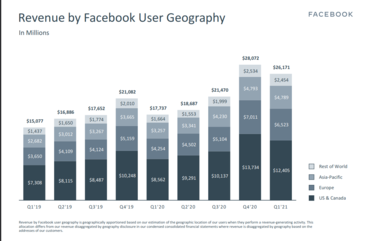

At the Guardian, Dan Milmo reports that 25% of its total, or $19 billion in 2021. Meta says it will appeal the against the decision, that in any case noyb's interpretation is wrong, and that the decision relates "only to which legal basis" Meta uses for "certain advertising. And, it said, carefully, "Advertisers can continue to use our platforms to reach potential customers, grow their business and create new markets." In other words, like the repeatedly failing efforts to stretch GDPR to enable data transfers between the EU and US, Meta thinks it can make a deal.

At the International Association of Privacy Professionals blog, Jennifer Bryant highlights the disagreement between EDPP and the Irish DPC, which argued that Meta was not relying on user consent as the legal basis for processing personal data - the DPC was willing to accept advertising as part of the "personalized" service Instagram promises. The key question: can Meta find a different legal basis that will pass muster not only with GDPR but with the Digital Markets Act, which comes into force on May 2? Meta itself, in a blog post includes personalized ads as a "necessary and essential part" of the personalized services Facebook and Instagram provide - and complains about regulatory uncertainty. Which, if they really wanted it, isn't so hard to achieve: comply with the most restrictive ruling and the most conservative interpretation of the law, and be done with it.

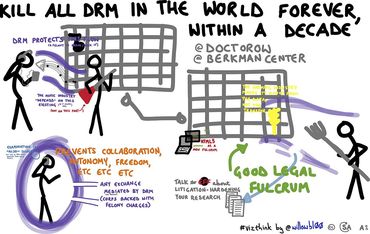

At Wired, Morgan Meaker argues that the threat to Meta's business model posed by the EDPB's ruling may be existential for more than just that one company. *Every* Silicon Valley company depends on the "contract" we all "sign" (that is, the terms and conditions we don't read) when we open our accounts as a legal basis for whatever they want to do with our data. If the business model is illegal for Meta, it's illegal for all of them. The death of surveillance capitalism has begun, the headline suggests optimistically.

The reality is most most people's tolerance for ads is directly proportional to their ability to ignore them. We've all learned to accept some level of advertising as the price of "free" content. The question here is whether we have to accept being exploited as well. No amount of "relevance" improves ads' intrusiveness for me. But that's a separate issue from the data exploitation none of us intentionally sign up for.

The "1984" Apple Super Bowl ad (YouTube) encapsulates the irony of our present situation: the price of viewing football at the time, it promised a new age in which information technology empowered us. Now we're in the ad's future, and what we got was an age in which information technology has become something that is done to us. This ruling is the next step in the battle to reverse that. It won't be enough by itself.

Illustrations: Image of Facebook logo.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Mastodon or Twitter.

For the last five years a laptop has been whining loudly in my living room. It hosts my mail server.

For the last five years a laptop has been whining loudly in my living room. It hosts my mail server.

Bad ideas never die.

Bad ideas never die.

The slight reopening of international travel - at least inbound to the UK - is reupping discussions of vaccination passports, which we last

The slight reopening of international travel - at least inbound to the UK - is reupping discussions of vaccination passports, which we last

-thumb-370x277-1083.jpg)

-thumb-270x360-798.jpg)

It was while I was listening to Isabella Henriques talk about

It was while I was listening to Isabella Henriques talk about  Advertisers, like some religions, aim to capture children's affections young, on the basis that the tastes and habits you acquire in childhood are the hardest for an interloper to disrupt. The food industry has long been notorious unhealthy foods into finding ways around regulations that limit how they target children on broadcast and physical-world media. But the internet offers new options: "Smart" toys are one set of examples; Facebook's new

Advertisers, like some religions, aim to capture children's affections young, on the basis that the tastes and habits you acquire in childhood are the hardest for an interloper to disrupt. The food industry has long been notorious unhealthy foods into finding ways around regulations that limit how they target children on broadcast and physical-world media. But the internet offers new options: "Smart" toys are one set of examples; Facebook's new