The virtuous patient

It's interesting to speculate about whether our collective approach to cybersecurity would be different if the dominant technologies hadn't been developed under the control of US companies. I'm thinking about the coronavirus, which I fear is about to expose every bit of the class, race, and economic inequality of the US in the most catastrophic way.

It's interesting to speculate about whether our collective approach to cybersecurity would be different if the dominant technologies hadn't been developed under the control of US companies. I'm thinking about the coronavirus, which I fear is about to expose every bit of the class, race, and economic inequality of the US in the most catastrophic way.

Here in Britain, the question I'm most commonly asked has become, "Why do Americans oppose universal health care?" This question is particularly relevant as the Democratic primaries bed down into daily headlines and pundits opining on whether "democratic socialist" Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who both favor "Medicare for All", are electable. How, UK friends ask, could they not be electable when what they're proposing is so obviously a good thing? How is calling health care a human right "socialist" rather than just "sane"? By that standard, Europe is full of socialist countries that are functioning democracies.

I respond that framing health insurance as an aspirational benefit of a "good job" was a stroke of evil genius that invoked everyone's worst meritocratic instincts while putting employers firmly in the feudal lord driving seat. I find it harder to explain how "socialist" became equated with "evil". "Socialized medicine" apparently began as a harmless description but in the 1960s the American Medical Association exploited it to scare people off. I thought doctors were supposed to first, do no harm?

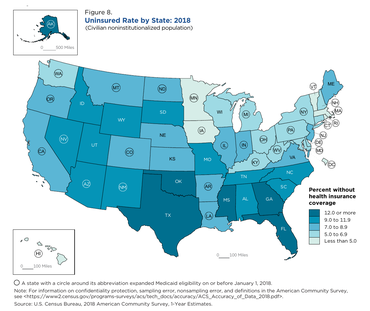

Of course, a virus doesn't care who's paying for health care - the real crux of the debates - but it also doesn't care if you're rich, poor, upper crust, working class, Republic, Democrat, or a narcissist who thinks expertise is vastly overrated and scientists are just egos with degrees. The consequence of treating health care as an aspirational benefit instead of a human right is that in 2018 27.5 million Americans had no health insurance. As others have noticed, uninsured people cluster in "red" states. Since Donald Trump took office, however, the number of uninsured is slowly regrowing.

Some of the uninsured are undoubtedly people who are homeless, but most are from working families. They work in gas stations and convenience stores, as agency maids and security guards, as Uber drivers, and...in food service. Skeleton staffing levels mean bosses penalize anyone trying to call in sick; low wage levels make sick days an unaffordable "luxury"; without available child care, kids must go to school, sick or well. Every misplaced incentive forces this group to soldier on and to avoid doctors as much as possible. The story of Ozmel Martinez Azcue, who did the socially responsible thing and got himself to a hospital for testing only to be billed for $3,270 (of which his share is $1,400) when he tested negative for coronavirus, is a horror story deterrent. As Carl Gibson writes at the Guardian, "...when you combine a for-profit healthcare system - in which only those wealthy enough to get care actually receive it - with a global pandemic, the only outcome will be unmitigated disaster".

This is a country where 40% of the population can't come up with an emergency $400, for whom no vaccine or test is "affordable". CDC's sensible advice is out of reach for the nearly 10% of the population whose work requires their physical presence; a divide throroughly exposed by 2012's Hurricane Sandy.

Sanity would dictate making testing, treatment, and vaccines completely free for the duration of the crisis in the interests of collective public health. But even that would require a profound shift in how Americans understand health care. It requires Americans to loosen their sense that health insurance is an individual merit badge and exercise a modest amount of trust in government - at a time when the man in charge is generally agreed to be entirely untrustworthy. As Laurie Garrett, the author of 1994's Pulitzer Prize-winning The Coming Plague, warned last month, two years ago Trump trashed the pandemic response teams Barack Obama put in place in 2014, after H1N1 and Ebola made the necessity for them clear.

If the US survives this intact, Trump will take the credit, but the reality will be that the country got lucky this time. Individuals won't, however; a pandemic in these conditions will soon be followed by a wave of bankruptcies, many directly or indirectly a consequence of medical bills - and a lot of them will have had health insurance. Plus, there will be the longer-term, hard-to-quantify damage of the spreading climate of fear, sowing distrust in a society that already has too much of it.

So back to cybersecurity and privacy. The same type of individualistic thinking underlies computer and networking designers who take the view that securing them is the individual problem of each entity that uses them. Individual companies have certainly improved on usability in some cases, but even the discovery of widespread disinformation campaigns has not really led to a public health-style collective response even though pervasive interconnection means the smallest user and device can be the vector for infecting a whole network. In security, as in health care, information asymmetry is such that the most "virtuous patient" struggles to make good choices. If a different country had dominated modern computing, would we, as Americans tend to think, have less, or no, innovation? Or would we have much more resilient systems?

Illustrations: The map of uninsured Americans in 2018, from the US Census Bureau.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.