Conventional wisdom

One of the problems the internet was always likely to face as a global medium was the conflict over who gets to make the rules and whose rules get to matter. So far, it's been possible to kick the can down the road for Future Government to figure out while each country makes its own rules. It's clear, though, that this is not a workable long-term strategy, if only because the longer we go on without equitable ways of solving conflicts, the more entrenched the ad hoc workarounds and because-we-can approaches will become. We've been fighting the same battles for nearly 30 years now.

One of the problems the internet was always likely to face as a global medium was the conflict over who gets to make the rules and whose rules get to matter. So far, it's been possible to kick the can down the road for Future Government to figure out while each country makes its own rules. It's clear, though, that this is not a workable long-term strategy, if only because the longer we go on without equitable ways of solving conflicts, the more entrenched the ad hoc workarounds and because-we-can approaches will become. We've been fighting the same battles for nearly 30 years now.

I didn't realize how much I longed for a change of battleground until last week's Internet Law Works-in-Progress paper workshop, when for the first time I heard an approach that sounded like it might move the conversation beyond the crypto wars, the censorship battles, and the what-did-Facebook-do-to-our-democracy anguish. The paper was presented by Asaf Lubin, a Yale JSD candidate whose background includes a fellowship at Privacy International. In it, he suggested that while each of the many cases of international legal clash has been considered separately by the courts, the reality is that together they all form a pattern.

The cases Lubin is talking about include the obvious ones, such as United States v. Microsoft, currently under consideration in the US Supreme Court and Apple v. FBI. But they also include the prehistoric cases that created the legal environment we've lived with for the last 25 years: 1996's US v. Thomas, the first jurisdictional dispute, which pitted the community standards of California against those of Tennessee (making it a toss-up whether the US would export the First Amendment Puritanism); 1995's Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy, which established that online services could be held liable for the content their users posted; and 1991's Cubby v. CompuServe, which ruled that CompuServe was a distributor, not a publisher and could not be held liable for user-posted content. The difference in those last two cases: Prodigy exercised some editorial control over postings; CompuServe did not. In the UK, notice-and-takedown rules were codified after the Godfrey v. Demon Internet extended defamation law to the internet..

The cases Lubin is talking about include the obvious ones, such as United States v. Microsoft, currently under consideration in the US Supreme Court and Apple v. FBI. But they also include the prehistoric cases that created the legal environment we've lived with for the last 25 years: 1996's US v. Thomas, the first jurisdictional dispute, which pitted the community standards of California against those of Tennessee (making it a toss-up whether the US would export the First Amendment Puritanism); 1995's Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy, which established that online services could be held liable for the content their users posted; and 1991's Cubby v. CompuServe, which ruled that CompuServe was a distributor, not a publisher and could not be held liable for user-posted content. The difference in those last two cases: Prodigy exercised some editorial control over postings; CompuServe did not. In the UK, notice-and-takedown rules were codified after the Godfrey v. Demon Internet extended defamation law to the internet..

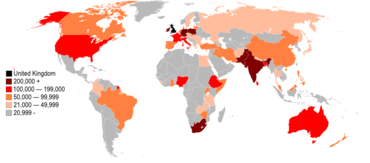

Both access to data - whether encrypted or not - and online content were always likely to repeatedly hit jurisdictional boundaries, and so it's proved. Google is arguing with France over whether right-to-be-forgotten requests should be deindexed worldwide or just in France or the EU. The UK is still planning to require age verification for pornography sites serving UK residents later this year, and is pondering what sort of regulation should be applied to internet platforms in the wake of the last two weeks of Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandals.

The biggest jurisdictional case, United States v. Microsoft, may have been rendered moot in the last couple of weeks by the highly divisive Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act. Divisive because: the technology companies seem to like it, EFF and CDT argue that it's an erosion of privacy laws because it lowers the standard of review for issuing warrants, and Peter Swire and Jennifer Daskal think it will improve privacy by setting up a mechanism by which the US can review what foreign governments do with the data they're given; they also believe it will serve us all better than if the Supreme Court rules in favor of the Department of Justice (which they consider likely).

Looking at this landscape, "They're being argued in a siloed approach," Lubin said, going on to imagine the thought process of the litigants involved. "I'm only interested in speech...or I'm a Mutual Legal Assistance person and only interested in law enforcement getting data. There are no conversations across fields and no recognition that the problems are the same." In conversation at conferences, he's catalogued reasons for this. Most cases are brought against companies too small to engage in too-complex litigation and who fear antagonizing the judge. Larger companies are strategic about which cases they argue and in front of whom; they seek to avoid having "sticky precedents" issued by judges who don't understand the conflicts or the unanticipated consequences. Courts, he said, may not even be the right forums for debating these issues.

The result, he went on to say, is that these debates conflate first-order rules, such as the right balance on privacy and freedom of expression, with second-order rules, such as the right procedures to follow when there's a conflict of laws. To solve the first-order rules, we'd need something like a Geneva Convention, which Lubin thought unlikely to happen.

To reach agreement on the second-order rules, however, he proposes a Hague Convention, which he described as "private international law treaties" that could address the problem of agreeing the rules to follow when laws conflict. As neither a lawyer nor a policy wonk, the idea sounded plausible and interesting: these are not debates that should be solved by either "Our lawyers are bigger and more expensive than your lawyers" or "We have bigger bombs." (Cue Tom Lehrer: "But might makes right...") I have no idea if such an idea can work or be made to happen. But it's the first constructive new suggestion I've heard anyone make for changing the conversation in a long, long time.

Illustrations: The Hague's Grote Markt (via Wikimedia; Asaf Lubin.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.