Wild things

"It's the things we can't predict that are going to further revolutionize what happens in wireless," the FTC's Julius Knapp said this week. He was speaking at the 5G Huddle, one of a pride, or perhaps a glamor, of such events this month in London alone. What two years ago was a shapeless ball of vague ideas is finding some common design themes.

"It's the things we can't predict that are going to further revolutionize what happens in wireless," the FTC's Julius Knapp said this week. He was speaking at the 5G Huddle, one of a pride, or perhaps a glamor, of such events this month in London alone. What two years ago was a shapeless ball of vague ideas is finding some common design themes.

The people debating the tradeoffs of latency, bandwidth, and coverage didn't include consumer groups, civil society, or anthropologists to represent ordinary humans - Ofcom was the closest. As Michael Froomkin has often said with respect to We Robot, early design decisions are crucial because they're so hard to shift once there's a legacy installed base. Hence the interest of the 5G Huddle: this is where prospective definitions are being compared.

In some ways the most interesting presentation was that of Sarah Weller, managing director of Mubaloo, the only speaker to discuss software and the closest to a representative of "us", prospective users. She wants support for her customers' desires: what "we" want, she said, is cars that detect imminent failures and book their own service appointments, software agents that send their owner to the doctor when they detect elevated heart rate and temperature; efficiency; reduced "admin"; and personalization. Younger generations, she said, "don't want to have stuff in front of them that they don't want to see. They want their experiences to be about them." Younger generations always want that; then they have kids and it's ha, ha, you lose.

Weller's most frequently-expressed desire from 5G is "now". "Proactive prompting about information we don't even know we need," she said. But how does that translate into technical specifications? Constant connectivity, or low latency? Universal coverage or higher speed? Philip Marnick, group director for spectrum at Ofcom, noted a switch: people used to climb remote hills in Wales to get away from it all. "Now they complain when their smartphones can't access maps." In that case, "now" means never having to prepare in advance for anything.

Weller's most frequently-expressed desire from 5G is "now". "Proactive prompting about information we don't even know we need," she said. But how does that translate into technical specifications? Constant connectivity, or low latency? Universal coverage or higher speed? Philip Marnick, group director for spectrum at Ofcom, noted a switch: people used to climb remote hills in Wales to get away from it all. "Now they complain when their smartphones can't access maps." In that case, "now" means never having to prepare in advance for anything.

At this event in 2014, I fretted about the impact on the internet of a mobile industry with quite different traditions and the arrogance of an industry whose people seemed to feel that whatever the internet community thought was dwarfed by the sheer numbers of mobile phones being sold. Even then, some recognized that a lot of people want smartphones because they provide mobile internet access, not because ooh, look! cellular! Underneath Weller's world, where people text or email silently and asynchronously with their friends, but speak intimately to their phones expecting a response in real time, is a requirement for masses of mobile data as all that speech is forwarded to cloud servers for processing and the results sent back. Plus, of course, there's video streams, rapidly escalating in quality, and that's without augmented reality, virtual reality...

For those who were around at the beginning of the internet, when the telcos were the enemy of innovation, and who have since seen mobile network operators try to corral their users into walled gardens, the collision of these worlds is unnerving. But it sounds like sense when Andy Sutton, a principal network architect at BT, says that the internet's existing protocols, designed decades ago for "best-effort" delivery and forgiving services like email, IRC, and FTP, may not be up to 21st century demands. What he hopes, he explained, is that the communities will collaborate on a "holistic" vision to create new networking protocols: better, more efficient, more energy-efficient, lower-latency, and more secure. Given those, then surely the internet community would want to adopt them.

Here, and a few weeks ago at the Westminster eForum event on spectrum allocation, Ofcom's Philip Marnick pitched heterogeneous networks that produce the perception of "everywhere and always there", even if it's not quite the reality. Sure: as long as you have the map when you want it without unexpected charges you don't care how you got it. Marnick's pet subject is the need for collaboration among service providers who are not used to considering each other's technical needs when designing their systems. "I don't know any operator who thinks about not pointing an antenna south because it might cause interference," he said by way of example, reminding me of my neighbor whose satellite dish had to be moved because a nearby tree grew to interfere with its line of sight.

Here, and a few weeks ago at the Westminster eForum event on spectrum allocation, Ofcom's Philip Marnick pitched heterogeneous networks that produce the perception of "everywhere and always there", even if it's not quite the reality. Sure: as long as you have the map when you want it without unexpected charges you don't care how you got it. Marnick's pet subject is the need for collaboration among service providers who are not used to considering each other's technical needs when designing their systems. "I don't know any operator who thinks about not pointing an antenna south because it might cause interference," he said by way of example, reminding me of my neighbor whose satellite dish had to be moved because a nearby tree grew to interfere with its line of sight.

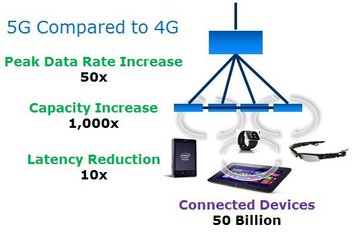

As far as I can work out, to a large extent the point of 5G really isn't you in specific or people in general. Even the attendee who said with exasperation that 4G isn't good enough because it wasn't really designed for data and "I want DATA", is a minority user. What they're building is the infrastructure for the Internet of Things. This has profound implications because until now we've measured coverage as a percentage of population, which has often meant that for people living in remote farmhouses mobile networks have been among the things they're remote from. We're now talking about coverage as a percentage of the land mass.

"We cannot limit ourselves to old models," Knapp said. No one imagined apps when 4G was being designed. By extension - he didn't say - we think we're designing 5G for machines. We might be entirely wrong.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

-thumb-240x251-113.jpg)

Now that the FBI has

Now that the FBI has

"Robots will only take over the world if we tell them how to do it," said Bill Smart at this year's

"Robots will only take over the world if we tell them how to do it," said Bill Smart at this year's  You can say to a human, "Drive at a reasonable speed" and usually trust the human's concept of "reasonable speed" is similar to yours. To a computer - robot - you have to specify the limits of "reasonable" to within a millimeter. This sort of thing, he said, is why robotics is hard.

You can say to a human, "Drive at a reasonable speed" and usually trust the human's concept of "reasonable speed" is similar to yours. To a computer - robot - you have to specify the limits of "reasonable" to within a millimeter. This sort of thing, he said, is why robotics is hard.